In 1947, San Francisco almost lost its Powell cable cars forever. A women-led campaign overcame male-dominated government and business interests to save them. That is a great story in itself. But there’s more to it, including lessons for today and tomorrow.

From techie to timeworn

When the Powell Street cable car lines opened in 1888, cable cars were the dominant form of high technology urban transportation. Within a few years, though, their place at the top of the techie totem pole was taken by electric streetcars and they became a niche technology to use on hills. After Seattle shut down its last cable line in 1940, only San Francisco had cable cars in the United States.

To the private companies that owned them, cable operations had become money pits, with their small capacity, a required two-person crew, and a complicated and cranky underground propulsion system that they did the minimum to maintain. The cable cars had many local fans, to be sure, regular riders who used them for actual daily transportation. But when lines were threatened with shutdown in the early 1940s, there were few to-the-barricades defenders. Our namesake Market Street Railway Company (MSRy) was able to kill off two cable lines—Castro Hill and Sacramento-Clay—plus the Fillmore Hill cable-assisted counterbalance line, in 1941-42.

MSRy still operated its two lines on Powell Street, but it might have taken them out too, had World War II not frozen US transit in place for the duration. (Another private company, the financially fragile California Street Cable Railroad (Cal Cable), operated cable lines on California Street, as well as O’Farrell, Jones & Hyde Streets.)

Visitors in the early 1940s found the cable cars quaint, but not quite iconic. Travel films and brochures from the period included the cable cars in their overview of San Francisco, but they weren’t given any more prominence than attractions like the flower stands around Union Square, Market Street with its four sets of streetcar tracks, Chinatown, Fisherman’s Wharf and, of course, the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges, then new.

The bulk of promotional attention given to the cable cars in those days went to the Powell lines, and specifically to the operation of the turntable at Powell and Market, seen as a novelty. (Cal Cable used double-end cars, so no turntables needed.) It’s fair to say cable cars didn’t have anywhere near the cachet that was to come.

“A bunch of junk”

When San Francisco’s city-owned Municipal Railway (Muni) bought out the much bigger MSRy in September 1944, the Powell cable car lines were part of the package. The buyout had been a key campaign goal of Mayor Roger Lapham, the Harvard-educated shipping executive who took office in January 1944, on a platform of “progress” and modernization, and pledging to serve only a single term.

Lapham knew the decrepitude of MSRy. Heavy wartime use and a lack of maintenance made both MSRy’s streetcar and cable car operations rickety; its finances were in desperate shape.

Some context is needed here to understand Lapham’s mindset. Voters had turned down four separate takeover attempts in the previous few years, but Lapham knew MSRy’s extensive route system couldn’t be allowed to collapse, as it served huge chunks of the city that Muni didn’t. Achieving his “progress” goals required consolidating and modernizing the transit system. He convinced voters to say yes to the takeover in June 1944 and personally operated the first streetcar of the combined system. (Earlier in 1944, during the takeover campaign, Lapham personally operated a horse car up Market Street as a stunt to draw attention to the need to “modernize” transit. Some accounts mistakenly mention that stunt as part of the 1947 cable car war.)

Having accomplished the takeover, Lapham still faced a dilemma. For decades, San Franciscans had been told that “their” Muni, America’s first publicly-owned big city transit system, completely paid for itself from riders’ fares, focusing on public service rather than profit (a dig at MSRy, which inherited a bad reputation from its predecessor, anti-labor, Chicago-based United Railroads). But Muni’s finances had been slipping like MSRy’s, reflecting a nationwide trend of transit agencies (still mostly privately owned) nearing bankruptcy, bedeviled by worn-out infrastructure they couldn’t afford to replace, fares kept artificially low by regulators, and the growing affordability of and desire for private automobiles, which contributed to dramatically declining postwar ridership. Still, voters expected transit to stay cheap while functioning well.

In an initial attempt to rationalize the combined system and effect economies, a 1945 study for Muni’s governing body, the city’s Public Utilities Commission, recommended retaining thirteen streetcar routes, rebuilding the tracks, and equipping them with 313 new PCC streetcars, relying on buses elsewhere but retaining the Powell cables. However, Muni’s operators’ union was staunchly opposed to removing the two-operator requirement for streetcars, making the operating costs of 313 PCCs unaffordable and tanking that plan.

While planning was underway, Lapham tackled his transit problem by trying to drive operating costs down where possible and adjusting fares upward. To him it was, after all, a business, even if owned by “the people.” Muni’s cash fare was raised from five cents to seven in 1944, and to ten cents in 1946. For doubling Muni fares in two years, Lapham was rewarded with a recall attempt, the first in the City’s history. He even signed the recall petition himself, welcoming the referendum on his actions. The recall fell short, but permanently tarnished his reputation. Meanwhile, transit service continued to deteriorate from service cuts and equipment failures.

Warning shot ignored

In mid-1945, Muni bosses said they doubted they could get enough operators to sign up on the Powell cable cars because the pay was the same as a bus driver got and the City was prohibited from paying more than the comparable wages paid by Cal Cable. Thus, the Powell cables might have to be shut down.

This caused a brief flurry of public pushback, led by the Women’s Chamber of Commerce, which called on San Franciscans to rally to the little cars’ defense, in part because “what would the boys in the service think if they came home and find we have allowed the cable cars to disappear?” (During the war, the cable cars had gained a following among soldiers and sailors passing through town, though overall ridership was overwhelmingly local.)

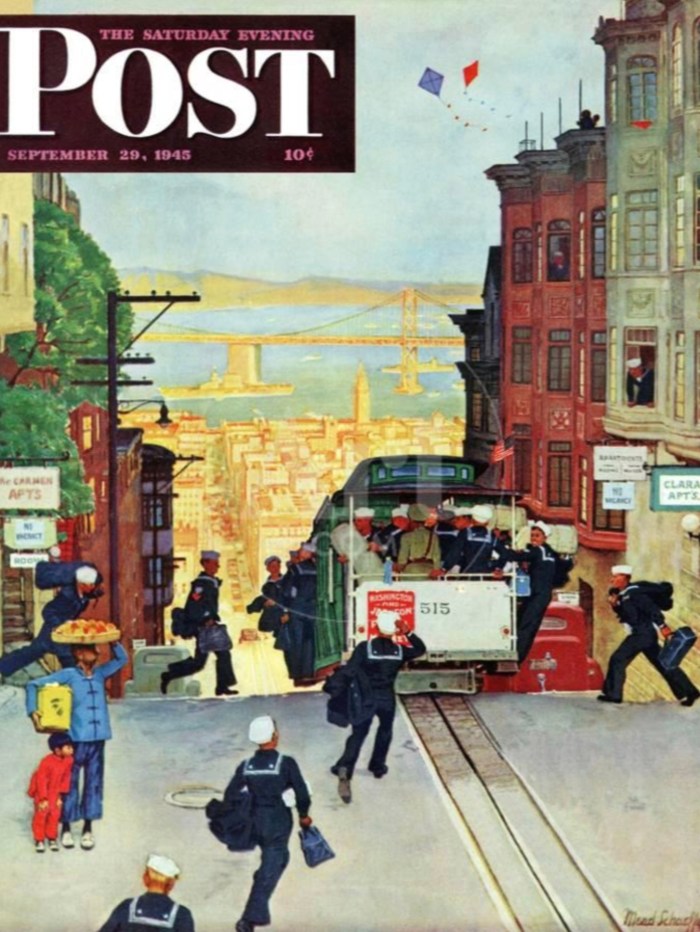

This image of returning servicemen inspired The Saturday Evening Post, one of nation’s most widely circulated and influential magazines, to put a Mead Schaeffer painting of a cable car on its cover shortly after V-J (Victory over Japan) Day in September 1945. The magazine then ran an article in February 1946 taking credit for “saving the cable cars” with that cover painting, which it said “helped touch off an explosive burst of civic pride.” And indeed there were letters and other entreaties, including a letter to the Chronicle from Sgt. Martin Sugarman on Iwo Jima, saying ‘Tear down the bay bridges, but leave our cable cars alone!’ When the operators’ signup occurred, it turned out Muni had no trouble fully staffing the cable cars, so the organizing capabilities of the Women’s Chamber of Commerce were never tested. It’s possible that Lapham then dismissed women’s ability to impact the issue.

Entering his final year in office, the mayor laid out a revised business case for overhauling Muni in his January 1947 State of the City speech to the Board of Supervisors. He became the first of many mayors to express frustration with the city’s transit system, most of which he had literally taken ownership of himself. “[Muni] is the number one headache of my administration,” he told the Board of Supervisors. He described the vast majority of transit vehicles as “a bunch of junk,” and said the car barns inherited from MSRy were “in deplorable shape.” His solution: placing bond issues on that November’s ballot to replace all but seven streetcar lines with buses (mostly electric trolley buses) that required just one operator, greatly saving on labor costs. Other improvements were promised too.

Oh, by the way…

Tossed into the mix (like a hand grenade) was this: Lapham called on Muni to scrap the Powell cable car lines “as soon as possible” because they were “old, outmoded, and inefficient, and do not belong in a modern transit system.” In fact, Lapham revealed, he had already ordered ten brand new streamlined gasoline buses from Twin Coach with dual engines to handle the Powell hills, and they were “on their way.” He presented this as a fait accompli, already decided, rather than as an issue for public consideration.

Pressed to explain how the mayor could order buses for the Powell lines when cable service hadn’t yet been abandoned, the top Muni executive, Public Utilities Commission General Manager James Turner, lied, stating the buses hadn’t been specifically bought for Powell, but then agreeing with Lapham that the buses would be phased in on Powell, starting on Sundays and gradually taking over.

Interestingly, Lapham didn’t include money to replace the Powell lines in that package. Instead, he paid for the new buses out of Muni’s thinly-stretched existing funds. Turner had reassured the public in 1945 that “[we] must look on a cable car as a family looks on a cranky and cantankerous grandpa—we can criticize his faults but you can bet your life we’re not going to trade the old man in on a new model.” Yet Lapham bulled past that and other earlier assurances to protect the Powell cars, stating the public had no right to question or vote on his decision.

Lapham’s plan to kill off the Powell cable cars without a vote of the people proved a spectacular miscalculation. As the boxer Mike Tyson said a half-century later, “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”

Who threw those haymakers that knocked out Lapham is a seminal story in San Francisco history and that of women’s empowerment.

Enter the “Cable Car Ladies”

San Francisco governance in 1947 was almost exclusively a white man’s club. So was its big business community. Lapham didn’t encounter strong opposition to his Powell plan from those quarters—at first anyway. Instead, pushback came from a group of women led by the president of the San Francisco Federation of the Arts, an umbrella group of various gardening, architecture, and arts groups.

That woman identified herself consistently in correspondence and speeches as “Mrs. Hans Klussmann,” just as the other (all white, mostly elite or “society”) women working with her used “Mrs.” and their husband’s first names to identify themselves. While this seems inconceivable today, it was the accepted style of the time, even in the media, which on the rare occasions they used Klussmann’s own first name, sometimes misspelled it as “Frieda” instead of the correct “Friedel.” What this signified, of course, was the widespread view that women did not have agency—or power—in their own right, but lived as reflections of their husbands’ status.

In the wake of Lapham’s bombshell announcement, women-led groups created the “Citizens’ Committee to Save the Cable Cars,” choosing Klussmann to head it. She proved to be a potent organizer with a gift for public relations, still a nascent field in those days. Where Lapham focused his argument for removal on the cost of providing continued cable service, Klussmann’s committee focused on the cost of losing the cable cars. In making that argument, she unlocked deep support for the little cars and at the same time elevated them into true iconic status, something they had not quite achieved before.

Klussmann wrote Lapham before the committee was even formed, asking his agreement on the uniqueness of the cable cars, which she said embody “so much distinctive charm and universal appeal.” She went on to ask Lapham: “Can you imagine London without Big Ben? Can you imagine Paris without the Eiffel Tower? Can you imagine New York without the Statue of Liberty? Can You imagine New Orleans without its French Quarter? Can you imagine San Francisco without its Cable Cars?”

Instead of attempting to mollify Klussmann, Lapham went out of his way to insult her, and those like her, with the sexist implication that they were “sentimentalists who do not have to pay the bills.” Klussmann volleyed by asking Lapham to sign her group’s petition himself. He responded, “the horse car had to go, the cable cars have to go…Waving petitions in the face of progress can no more stop it than could King Canute stop the waves by royal decree. Those of our citizens and visitors who take delight in bumping the bumps and riding the curves will have to find their enjoyment in the chutes, the scenic railway, or the ‘spinno-rocket’ at the beach.” Rubbing salt into what he must have presumed was a wound, he predicted that “San Francisco may adopt the atom-propelled bus even before the tears of the petitioners are dry.”

Arrogance undone

Lapham hoped to pre-empt public opposition by deploying the new buses to Powell Street as soon as they arrived, but was foiled by Powell Street itself. The downtown portion of Powell, including the steep incline on Nob Hill, was paved in brick, and the Chronicle story above questioned whether it would be safe for buses in wet weather. The Department of Public Works said they could repave it in concrete, but it would take a year.

What Lapham actually accomplished, of course, was throwing gasoline on the fire that Klussmann kindled. But rather than retreat, he tried to deflect. In a trial balloon almost certainly planted by the Mayor’s Office, the city’s most-read newspaper columnist, Herb Caen, wrote on January 30, “About those cable cars: The Powell St. line is a plucked duck, that’s for sure. But keep tabs and see if the situation doesn’t boil down to this eventually: The Calif. St. line will be kept in operation, for tourists and sentimentalists, at greatly increased fare–maybe as high as 20 cents a ride.”

The City didn’t own the California Street company’s lines at that time, but not coincidentally, in early March, Lapham’s hand-picked “administrative transportation planning council” recommended that the City propose a separate bond issue to buy the financially failing Cal Cable and retain a small portion of the trackage, aimed primarily at tourists. Lapham said he agreed.

It wasn’t enough.

Powell vs. Cal

It is certainly no coincidence that the same prominent businesses that supported Klussmann’s campaign to save the Powell cars refused to take Lapham’s bait of saving the California cable line instead. Powell Street cut through the heart of the downtown retail district centered on Union Square. The Powell-Market turntable was close to the City’s biggest department stores. The Powell-Mason line reached Fisherman’s Wharf, already a tourist destination. The Washington-Jackson line served Pacific Heights, home to affluent shoppers.

By contrast, Cal Cable’s California Street line missed downtown entirely. While its O’Farrell, Jones & Hyde line did reach Union Square-area retailers, the other end of the line, Aquatic Park, was then factories, warehouses, and dirt lots. (Ghirardelli Square and other attractions didn’t come to fruition until the Washington-Jackson line was rerouted onto Hyde in 1957.)

Beyond those considerations, there was the special appeal of the turntable at Powell and Market, needed to turn the single-end Powell cars. (Double-end Cal Cable cars reversed with a simple switch.) Travelogues featuring the cable cars invariably began with shots of the conductor and gripman pulling and pushing the cable car around the turntable, often assisted spontaneously by citizens (including, as a boy, this author). Photographers who later gained wide fame, such as Fred Lyon and Max Yavno, captured this simple act. Postcards of the turntable proliferated. San Franciscans, too, had more familiarity with the Powell lines because of the turntable’s strategic location at one of the busiest blocks in the City. Lapham’s fallback substitute strategy didn’t work.

Herb Caen had already seen the wind change, and a week after he floated the trial balloon, wrote, “Roger Lapham’s dictum that ‘cable cars must go’ has been good for one thing, anyway—more publicity than the village has received since the er-uh-thquake; practically every newsmag and newspaper in the country has printed the darn yarn at great length.” Indeed, Life magazine, one of the nation’s most influential publications, ran a six-page photo spread on the cable cars in late March, and other national publications followed suit, some portraying Lapham as heartless.

Politicians began feeling the heat as Klussmann and her Committee quickly fanned the flames, in two ways. First, she refuted the claims made by Turner and the PUC about the excessive cost of cable car operation with facts and figures indicating they were a worthwhile investment and similarly parried claims they were unsafe with statistics showing otherwise. This eroded some of Lapham’s early business support. Then, the Committee set off a flurry of activity portraying the cable cars as adorable ambassadors for San Francisco, elevating their status.

“Ritzy rummage sale”

Klussmann and the Committee ran a master class in shaping public opinion. To remind San Franciscans of the human aspect of cable car history, they honored three retired gripmen who had piloted cable cars on Market Street before the 1906 earthquake, inviting the press to watch them sign their petitions and recount their personal stories at the Committee’s inaugural event. They raised money with events like a “ritzy rummage sale” with high quality clothing and items donated by wealthy society women. They scattered petition-signing booths around downtown, appealing to both retail businesses and shoppers with displays of how cable cars could effectively be represented in merchandise and used in advertising campaigns. Both Macy’s and The Emporium responded with cable car print dresses, which sold briskly among the women who were key targets of the Committee. The Committee sponsored a beauty contest (a surefire publicity tool of the day) with “winners” representing each cable car line. All kinds of cable car souvenirs were quickly turned out by businesses looking to profit from the controversy.

Richard Gump, president of the high-end Union Square store that bore his family name, took out a national ad in Time magazine asking readers to vote on whether to save the Powell cars. He was overwhelmed with positive responses from all over the country, enhancing the stature of his business as its own kind of San Francisco icon.

The Citizens’ Committee arranged for photo ops with celebrities of the day who passed through town, expressing their love for the cable cars. Even Eleanor Roosevelt, the former first lady and an influential newspaper columnist, gave the Powell cars a plug.

PUC pushback

The PUC didn’t just roll over for Klussmann. They offered free rides on one of the Twin Coaches in an attempt to demonstrate their superiority over the cable cars. Recognizing that Klussmann’s campaign focused on women, the PUC worked to attract women to ride the new buses, emphasizing their comfort and safety. The anti-cable car San Francisco News showed up to cover the effort. The article, as recounted by urban scholar Damon Scott in a 2014 research paper, recounted two female riders’ reactions: “At the base of one of the steepest hills, Mrs. Paul Cheader ‘clutched her pocketbook tightly in both hands, and a look of fright came over her face,’ but when the driver started up the hill—‘smoothly…engines purring with confidence’—she relaxed and smiled. At the end of the trip, ‘with lady-shopper wisdom,’ she commented, ‘I think it’s very good.’”

The News then assigned one of the city’s only female reporters, Sydney Ayers, to drive one of the new buses, which she proclaimed in print was “so simple a child can drive them.” Or as the condescending tone of the article implied, even a woman. The story ran on the front page of the paper, with two photographs. Damon Scott surmised that the PUC’s intent was to show that “cable car supporters were antimodern reactionaries who were not giving the buses a fair hearing.” He notes that Klussmann’s crusade forced the all-male coterie of San Francisco transit executives to pay serious attention to the opinions and desires of women, who formed the bulk of mid-day ridership.

Still, Lapham persisted in his claim that he, through the PUC he controlled, could get rid of the cable cars without a vote of the people, which is what the reasonable-appearing and genteel Mrs. Klussmann was asking for.

This did not sit well with many. Within two weeks of Lapham’s State of the City speech, Supervisor Marvin Lewis (later a moving force behind BART, and grandfather of Salesforce Founder Marc Benioff) suggested the matter be put to a public vote. Other politicians soon joined. The City Attorney ruled that citizens did indeed have the right to place cable car protection on the ballot, and on May 5, the Board of Supervisors voted 7-4 to do just that, as Proposition 10.

At this point, any savvy politician would have groped for a life preserver. Instead, Lapham continued his Grinch-like grumbling against the Powell cable cars as his popularity plummeted. The mounting national media coverage and the outpouring of local love for the Powell lines had suddenly and dramatically raised the profile of the city’s cable cars. Now, instead of being seen as just one of several equal visitor attractions in the City, their only real rival was the Golden Gate Bridge. This was the result of both Klussmann’s brilliant organizing effort, positioning the cable cars as an essential component of San Francisco’s culture as well as history, and Lapham’s condescending bullying and denigration of the women leading the fight.

Lapham at least must have understood that the swelling tsunami of opposition to his cable car assassination attempt could swamp his transportation bonds as well, passage of which he saw as a centerpiece of his legacy as mayor. As it became clear that voters would save the Powell cables, PUC General Manager Turner specifically stated that if both the Transportation Bonds and the Cable Car preservation measure passed in November, part of the bond issue proceeds would go toward complete reconstruction of the Powell Street lines.

The People speak

Sharing the November ballot with the cable car measure and the transportation bonds was, almost as an aside, an open race for Mayor, since Lapham had limited himself to one term (had he not, the voters certainly would have).

One mayoral candidate in particular, Judge Elmer Robinson, portrayed himself as the anti-Lapham (without of course ever mentioning that increasingly reviled name). No chilly businessman he, Robinson repeatedly said, “I am a candidate with a good heart.” Whenever he could squeeze in a photo op with the city’s increasingly popular symbol, he did. He went further with a statement saying “My whole heart is for the cable cars. Besides being a symbol of San Francisco’s picturesque life and traditions, the cable cars are still most useful and effective on our hills and the people in a large majority would much rather ride on them than on an oil-burning bus.”

On November 4, 1947, San Francisco voters elected Robinson mayor, passed Lapham’s transportation bonds (which in the next three years transformed Muni), and, most famously, saved the Powell cable cars by a large majority indeed, 166,989 ‘Yes’ to 51,457 ‘No’; better than a 3-1 margin.

Not everyone cheered. Notably, the San Francisco Chronicle, which had displayed a notable anti-cable car bias in its news stories throughout the campaign, reported on the election victory thus: “It was a victory of sentiment over cost sheets and the opinions of transportation engineers.” (In a 2021 article entitled “A shame revealed: that time the Chronicle tried to kill the cable cars,” the paper’s culture critic, Peter Hartlaub, recounted and denounced his newspaper’s 1947 coverage, describing it as “pure weaseliness…a sort of Grand Moff Tarkin to Lapham’s Darth Vader.”)

Promise unkept

Despite the PUC’s promise that the successful bond issue would pay for reconstruction of the Powell lines, estimated to cost between $250,000 (an estimate Klussmann obtained from an outside contractor) and $750,000 (the PUC’s own estimate), only $15,000 of the bond issue’s $20 million proceeds were spent on the Powell lines, to replace the turntable at Powell and Market.

Muni did the minimum to keep the Powell cables running, even though they embraced public relations activities to take advantage of the increased visibility of the cars Klussmann’s committee had created. In 1948, the City enthusiastically accepted Western Pacific Railroad’s offer to send a Powell cable car to the Chicago Railroad Fair, a huge event. Car 524 (now 24, and dedicated to Willie Mays) actually ran along a short cable setup on the shores of Lake Michigan, where it was a star of the show, reaffirming San Francisco’s uniqueness in running them. To make sure fair visitors knew the provenance of the car, Muni painters replaced the lettering on the sides that just said “Municipal Railway” with “Municipal Railway of San Francisco.” Many Powell cars later received this lettering. Freshly rebuilt Powell Car 8 wears it today as a tribute to the era.

The personal visibility and stature Klussmann gained in leading the 1947 fight positioned her as a force to be feared by City leaders, helping her Committee apply continuing pressure on City leaders to buy the failing Cal Cable. A 1948 bond issue, endorsed by Mayor Robinson and the Board of Supervisors, garnered 59% support, falling short of the 2/3 required. The following year, voters approved a purchase that didn’t need bonds, thus requiring only a simple majority. Even so, it squeaked through with just 52%.

While the City was negotiating Cal Cable’s purchase in 1950, Klussmann encouraged Cal Cable’s efforts to bolster its finances by offering sponsorships of individual cars on the California and O’Farrell, Jones & Hyde lines, with full advertising rights, to businesses for $100/month. A Who’s-Who of local businesses who had supported Klussmann in 1947 answered the call, including Roos Brothers, Blum’s, The Emporium, Macy’s, Fisherman’s Grotto, and many others. This helped Cal Cable keep operating longer than it otherwise would have been able to.

To raise funds for the Committee, she presided over a huge ball at the Fairmont Hotel in 1950, calling it Cable Car Carnival. The next year, railroad historians Lucius Beebe and Charles Clegg took the name as the title of their popular book on the history of San Francisco’s cable cars, further cementing the little cars’ iconic status.

The cable cars needed all the idolatry they could get, because almost immediately after Muni’s takeover of Cal Cable in 1952, a second cable car war began, which yielded the truncated system we see today.

Legacy

Friedel Klussmann went on to found the nonprofit San Francisco Beautiful, which among many other achievements, still sponsors an art contest on Muni vehicles every year. She also helped gain City Charter protection and formed a support group called “Cable Car Friends,” which endured for decades, and whose last leader, Virgil Caselli (who raised private money for the 1980s rebuilding) asked our nonprofit to carry on its work. She campaigned for the passage of Proposition Q in 1981, which mandated minimum operating hours for the cable cars, protecting them from capricious cutbacks. As a young reporter, the author of this article interviewed Mrs. Klussmann numerous times at her Telegraph Hill home, finding her unfailingly gracious and modest to a fault about her accomplishments.

Those accomplishments went beyond the saving of the cable cars. By standing toe to toe with a bully male mayor and other condescending men in the City’s leadership, she demonstrated the power of organizing around a civic and political cause and the consequences to politicians of denigrating women’s voices. It was a lesson male politicians should have learned during the suffrage and prohibition movements of the late 1910s, but didn’t.

Klussmann’s leadership helped empower women in the Bay Area, and beyond, to take on larger challenges, such as saving San Francisco Bay from being filled and degraded. Three East Bay women, Catherine Kerr, Sylvia McLaughlin, and Ester Gulick, founded Save the Bay in 1961, following a similar playbook to Klussmann’s. Similar women-led organizations for other environmental, civic, and political causes sprang up around the country.

It’s important to note that these organizations and others resulted in part from the fact that in that era, women were shut out of the kind of management and organizing jobs their skills qualified

them for. In 1947, it had barely been a quarter-century since women had won the national right to vote. It’s also important to note because they were precluded from paid employment worthy of their skills, the women on the Citizens’ Committee to Save the Cable Cars had time to invest in the effort. Additionally, they were considered among the social elite, which carried influence through their husbands. Women without elite status and women of color in that time would not have been heard.

Klussmann’s coup helped women’s voices be heard in the civic arena, particularly in San Francisco. Government continued to try to jam through unpopular projects, sometimes with illegal tactics (as in the second cable car war of 1954), but public outcry, often led by women, prevailed in such crusades as the successful Freeway Revolt of the early 1960s. Public input gradually became a core requirement for any major government decision or project.

And women began to take their rightful place in the halls of City power itself. In 1982, it was San Francisco’s first female mayor, Dianne Feinstein, who personally led the campaign to save the cable cars all over again, when age and neglected maintenance finally caught up with the system. Friedel Klussmann, then in her mid-80s, played a visible, honored role in that campaign.

And though Feinstein came from the city’s elite (her late husband, like Klussmann’s, had been a surgeon), other women from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds were starting to climb the political ladder. Today, the cable car system’s biggest fan is the current mayor, London Breed, a Black woman raised in public housing.

When Klussmann died in 1986 at the age of 90, the cable cars themselves were draped in black to mourn her passing. In recognition of Klussmann’s achievements, Powell Cable Car 1 is dedicated to her, and 25 years ago, in 1997, Senator Dianne Feinstein led the dedication of the cable car turnaround in Aquatic Park to Friedel Klussmann, saying “she is looking down from the sky.”

Klussmann is also remembered through the wonderful children’s book, Maybelle the Cable Car, published in 1952 and popular with new generations of kids today. Author and illustrator Virginia Lee Burton tells the story of how a cable car named “Maybelle”—inspiring the nickname of today’s Powell Car 26—was threatened by a bus, given the male name Bill. The “City Fathers” wanted Bill, who they said represented “speed and progress,” to replace the “slow” cable car that “can’t be safe.” But, the book says, “one person said, ‘Why do we have to?’” and the people came together to save Maybelle and her friends. Lest there be any doubt who the “one person” was, Burton dedicated the book to Klussmann, “leading light in the fight to save them from extinction.”

One last thing. Remember that Mayor Lapham was characterized as heartless for trying to kill the Powell cables, and that his successor, Mayor Robinson, repeatedly said his whole heart was for the cable cars? Well, in 1953, Douglas Cross wrote the lyrics to “I Left My Heart in San Francisco,” which became Tony Bennett’s signature song. What symbolized the city’s heart to Cross? He didn’t mention the Golden Gate Bridge. Or Fisherman’s Wharf. Or Union Square. No, he singled out what in the preceding five years had come to define San Francisco around the world as the city where “little cable cars climb halfway to the stars.”

Mission accomplished, Friedel Klussmann. Thank you.

By Rick Laubscher, Market Street Railway President

Join us on Wednesday, October 26, 11 a.m., at the Powell and Market Cable Car Turntable to celebrate this 75th anniversary with a ride to Aquatic Park on the Hyde line.

If you like our exclusive content, please consider even a small donation to help our nonprofit.

Comments: 1