NOTE: This article was written for our member magazine, Inside Track, in 2013. Seven years later, after continuous planning for extensive changes to Market Street, City department heads announced there was no money available for most of the envisioned changes, due largely to the Covid-19 pandemic’s impact on city finances.

For more than a century and a half, San Francisco’s transit has centered on Market Street. Today, the design of Market Street for the next half-century is being decided. Many interests are competing for space on the future Market Street. It’s far from certain that transit, including the historic streetcars, will get top priority. Our organization is working hard to secure the best possible conditions for the F-line along the Market Street of the future.

“Given our name, Market Street Railway, it’s natural that we make our voice heard as clearly as possible on issues relating to the street we’re named for,” says Bruce Agid, chairman of MSR’s advocacy committee and leader of our advocacy efforts on the Better Market Street Project. “Part of the positive energy we bring to our advocacy is our historical perspective on Market Street.”

Boulevard from the beginning

Market Street was laid out by Jasper O’Farrell, the city’s first surveyor, in 1847, following the American conquest of the preceding year. The Mexican village of Yerba Buena had been centered on Portsmouth Square, at what’s now Kearny and Clay Streets. O’Farrell reconciled this north-south-east-west grid with the diagonal trail from the Bay to Mission Dolores (roughly along today’s Mission Street) by surveying what he called a “grand promenade” north of Mission, where the two conflicting street grids would meet. Its proposed 120-foot width seemed preposterously pretentious for a sleepy village, but the Gold Rush made the plan seem prescient, as tens of thousands of fortune seekers flooded the city, immediately building San Francisco into America’s preeminent Pacific port. This new main street was named for a counterpart in Philadelphia: Market Street.

From the beginning, Market’s positioning between two offset street grids made it the very spine of the city. As such, it has always been San Francisco’s main street, for transit as well as commerce. In 1860, a steam train provided the first rail transit on Market. Horse cars soon supplanted the noisy steam train, but the horses were largely eclipsed by cable cars in the 1880s. These expensive cable lines, owned by the all-powerful Southern Pacific Railroad, were the highest technology of their day. Five cable lines funneled onto Market from McAllister, Hayes, Haight, Valencia, and Castro Streets, spurring the creation of several new neighborhoods. (All but Valencia still host transit lines today, with the Castro route the ancestor of today’s F-line.)

Streetcars replaced cable cars on Market after the 1906 Earthquake and Fire. Immediately after its first line opened on Geary in 1912, Muni replicated what cable cars had done 30 years previously, building streetcar lines from less developed parts of the city to funnel onto Market Street. These lines—the J, K, L, M, and N—carried residents of these new neighborhoods to the critical mass of businesses and shops along the city’s main street.

These five Muni streetcar lines survived on the surface of Market until 1982, when they were placed in the new Muni Metro Subway under Market. They carried even more riders, who of course become pedestrians on Market when they exited the subway. (The F-line ultimately augmented these lines with surface streetcar service along Market, thanks in large measure to the advocacy of Market Street Railway’s early leaders.) Other long-time streetcar lines on Market survive today as buses, such as the 5, 6, 21, and 31.

Multiple makeovers

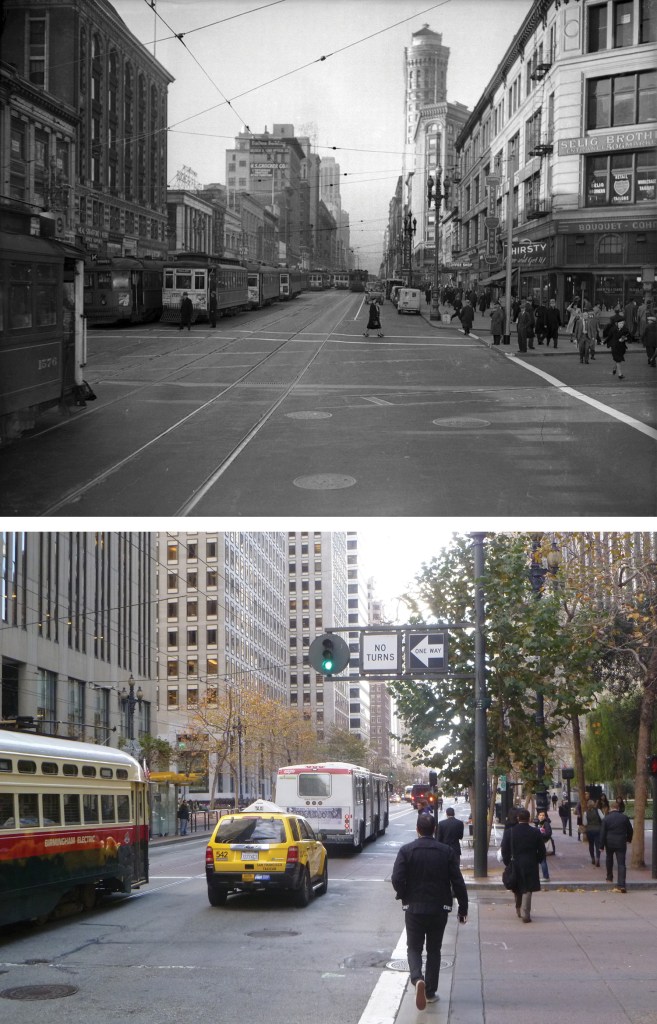

Market has experienced multiple makeovers in its 167-year history, but of necessity, transit has always been a constant. Beyond the mode shift (from one vehicle type to another), there have been at least three seminal events in Market’s transit history.

The first came in 1918, when Muni completed its own streetcar tracks alongside its private competitor’s, giving the street four lanes of transit, a feature enduring to this day (the outside tracks gave way to buses using that lane after World War II.)

The second makeover came with the construction of the two-level subway under Market in the 1960s and 70s. This brought BART, and with it, more high-rise offices, and workers to fill them, from Third Street east. But it also brought a physical reconfiguration of Market Street. Curbside parking was removed along with the outermost traffic lane and the already wide sidewalks were almost doubled in width. This grand plan also called for removal of all surface transit on Market except for diesel shuttle buses. Trolley coaches were to be rerouted off the street, all streetcars placed in the subway, and all overhead wires removed. But Muni riders rebelled and the trolley coaches and ultimately the streetcars stayed on Market.

The planners envisioned this new Market Street as a place for people to gather and relax as well as to walk. Market had never been much of a place for lingering as the sidewalks were always filled with people in transit. But now, expensive new ‘street furniture’ was installed, including enormous granite slabs at seat height in the widened area of the sidewalks, along with benches in two new pedestrian plazas on Market, Hallidie Plaza at Powell and United Nations Plaza where Fulton Street had been. Soon, however, it became clear that the main users of this new street furniture were panhandlers or homeless people, and over time, city officials removed the big granite slabs along with many of the benches. In this same period, though, several large plazas, open to the public, opened along Market Street as integral parts of new high-rise developments. (Today, there are almost 20 plazas open to the public on Market, or within a half-block, between Van Ness and the Ferry Building.)

The third major change in Market’s transit history comes with the rise of bicycle use. A new generation of San Franciscans relies heavily on bicycles for daily transportation. As with transit, Market Street has become a funnel for bicycle riders from neighborhoods to the west and south. The bicycle demand has led to installation of bike lanes from Franklin to Eighth Streets along with bike racks and other amenities. This, in turn, has driven even more demand. Muni’s parent, SFMTA, estimates the number of people riding bikes in the city has increased 14 percent since 2011 and 96 percent since 2006.

High stakes for transit

Deciding what happens next on Market is something of a tug-of-war between various interests. What’s at stake is how effectively the F-line and other Muni services will be able to operate on Market Street between Octavia Street and the Ferry Building. Bicycle and pedestrian access and safety are at stake as well. It’s all tied to what the City calls the “Better Market Street Project,” an effort that has grown from a simple repaving proposal to a multi-faceted, multi-city department process that has involved hundreds of citizens and dozens of stakeholder groups.

The project’s website, bettermarketstreetsf.org, states, “The goal of the project is to revitalize Market Street from Octavia Boulevard to the Embarcadero and reestablish the street as the premier cultural, civic and economic center of San Francisco and the Bay Area. The new design should create a comfortable, universally accessible, sustainable, and enjoyable place that attracts more people on foot, bicycle and public transit to visit shops, adjacent neighborhoods and area attractions.”

MSR Advocacy Committee Chair Bruce Agid and MSR President Rick Laubscher are working closely with other groups, including the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition, Walk SF (a pedestrian advocacy group) and the San Francisco Transit Riders Union, a new group standing up for Muni riders, to advocate win-win solutions that benefit all modes of travel.

Our common emphasis is on travel. “For more than 150 years, Market Street has been about motion,” Laubscher says. “It is literally our city’s main artery and we need to focus our efforts and resources to make it flow more efficiently, for transit riders, pedestrians, and bicyclists alike. If we compromise this goal for other considerations, we will be saddled with higher Muni operating costs and less safe conditions for bicyclists and pedestrians for decades to come.”

Primary among the “other considerations” Laubscher mentions is the emphasis that some city employees are putting on what they call “streetlife activation zones,” areas of sidewalk or adjacent public plazas that, according to planning documents, “provide space to activate Market Street with art, performances, seating, sidewalk cafes, parklets, and other social activities.”

“To be clear, we support vibrant but safe streetlife the entire length of Market Street,” Agid says. “We believe there’s plenty of room to do this by improving existing public plazas and other areas along the promenade without slowing down transit or compromising bicycle or pedestrian safety. And we see some areas of concern there that must be addressed through comprehensive planning and stakeholder review.”

For example, the project website’s front page states, in enlarged type, “Market Street needs to be more than a transportation route, it needs to be the city’s most vibrant public space and many San Franciscans feel it falls far short of this ideal” (emphasis in the original). This statement is not formal city policy, but it is being put forward as such anyway. While on one level this may not sound controversial, literally each foot of width on Market’s right-of-way has the potential to speed or slow transit, depending on how it is allocated. Top city transit officials have privately voiced their concerns to us that the priorities of other Market Street users (and their defenders) may trump transportation efficiency.

Safely accommodating surging bicycle use is a key issue, because it represents a relatively new, but quickly growing, part of the Market transportation mix.

Cycletracks?

The influential San Francisco Bicycle Coalition has been a strong advocate of cycletracks along the downtown section of Market Street. These are dedicated bicycle lanes separated from motor vehicle traffic for safety. One option for the Better Market Street Project would include continuous cycletracks from Van Ness Avenue to the Ferry Building, created mostly by taking the outer edge of the current sidewalks.

The near doubling of Market Street’s sidewalk widths in the 1970s didn’t much change pedestrian habits. The double rows of street trees, newspaper racks, and other “street furniture” near the curb has kept most pedestrians walking close to the buildings. Additionally, many vendors, some unauthorized, have set up tables on the widened portion of sidewalks, further impeding pedestrian flow. “Pedestrians have always gravitated toward the building fronts along Market,” Laubscher notes. “Given that long-standing preference, it seems to us there’s room for both cycletracks and adequate pedestrian space on almost every block of Market, as long as the sidewalks are kept reasonably clear.”

If the sidewalks hadn’t been widened 40 years ago, cycletracks would be a snap to install on Market. As it is, however, cutting back today’s sidewalks to install cycletracks on Market would be expensive, because city planners believe a large number of historic ‘Path of Gold’ streetlight poles, which also hold up the Muni overhead wires, would have to be relocated, along with fire hydrants and other utilities. (Market Street Railway’s own analysis indicates relatively few of the Path of Gold poles would actually require relocation with the proper design.)

Cost factors may explain why another bicycle option has been put forward by planners, with no apparent public demand, to put the cycletrack on Mission Street, a block south. Mission has numerous driveways and more side streets than Market. Mission also hosts heavy bus traffic, including the various versions of the 14-line, served almost exclusively by 60-foot articulated buses, plus regional bus service to the Peninsula (Samtrans) and the North Bay (Golden Gate Transit). All these buses would have to move off Mission to make room for the cycletracks, almost certainly to be relocated to Market Street.

“We believe the Mission Street cycletrack option should not have been considered at all. It is so flawed that we think it’s a waste of public money and time to include it in the EIS,” Laubscher told a Board of Supervisors hearing on the Better Market Street Project recently. “It seems clear to us that urban cyclists, especially bike commuters, will use Market anyway, in mixed traffic as they do today, yielding no improvement in bicycle safety or efficiency. And the extra buses that would be dumped on Market will slow down Muni service on that street, when the goal is to speed it up.”

Paring down cars

One travel mode that should be reduced on the downtown portion of Market Street: private automobiles. A test project to divert eastbound automobiles off Market at Tenth Street has reduced the time it takes buses, streetcars, and bicycles to move along the street and has been made permanent (though autos can turn back onto Market farther east). There is near-consensus among stakeholders that more restrictions should be placed on automobiles using Market Street, where there are no driveways or other compelling reasons for cars to be there.

Market Street Railway joins the Bicycle Coalition in supporting additional short-term automobile restrictions on Market Street, starting as soon as possible, to test the actual effect of various alternatives before investing large amounts of money in permanently reconfiguring traffic patterns.

But we must remember there will always be considerable regional traffic that has to cross San Francisco as well as a significant number of San Franciscans for whom transit is a poor option. Already, intersections such as First and Market are regularly blocked by crossing automobiles in the afternoon rush hour, snarling buses and streetcars, delaying transit users as well as presenting dangers to bicyclists and pedestrians. So, any changes must be carefully considered to allow cross traffic to flow across Market as safely and smoothly as possible.

Unintended impacts from street closures must also be considered. For example, the current working proposal envisions closing Ellis Street where it intersects Stockton and Market to create an additional ‘streetlife activation zone’ (although Hallidie and Yerba Buena Plazas are within a block and Union Square is just two blocks away. Closing Ellis would take away the shortest route across Market to the Bay Bridge and Peninsula from drivers leaving the busy Ellis-O’Farrell garage via Ellis. The likely result: more auto traffic on Powell Street, further slowing cable car service, and on O’Farrell, slowing down Muni’s busiest bus line, the 38-Geary.

It’s important to note, however, that this is still at the proposal state. All street modifications will be studied in the required environmental impact statement (EIS), with opportunities for public comment.

Quicker F-line service

While some may feel these issues are peripheral to improving F-line service, they all play a major role. Bicycles lacking their own safe lane must share the curb lane with Muni buses, which can in turn creep into the track lane where the F-line and other buses are. Adding more buses to Market, as a Mission Street cycletrack would, is another sure path to slow down transit on Market.

So for Market Street Railway, the priorities are avoiding negative impacts to transit, and even more importantly, promoting positive ones.

One such positive step, in our view, is reducing the number of F-line stops on the downtown portion of Market. On Upper Market (west of Haight), the F-line is the only local Muni service. The spacing between the Van Ness and Church Street underground Metro stations is abnormally long, and Mint Hill makes it tougher for many pedestrians to walk that extra distance to the Metro subway. So keeping the stops at every block on that portion of Market, as well as to the Castro, makes sense for the ‘neighborhood trolley’ portion of the F-line.

East of Van Ness, though, it’s a different story. There are multiple Muni bus lines that stop every block. Those that stop at the curb are particularly convenient for riders going only a block or two. People who use local buses to travel these short-distances along Market make more room for longer-distance riders on the (very crowded) F-line cars.

That’s why we agree with the idea of reducing the number of F-line stops from Van Ness to the Ferry Building. There are currently twelve in each direction. Different alternatives call for either nine or six in a revamped Market Street. If six were the number chosen, they would generally align with the Market Street BART/Metro stations (Embarcadero, Montgomery, Powell, Civic Center, Van Ness). Intermediate stops would be added with a nine-stop option.

It’s important to note that several of the current F-line stops would have to be moved anyway in a Market Street reconstruction. Several of them, including one of the busiest on the F-line (Wharf-bound at Fourth Street), are opposite BART escalator entrances, which can’t be moved. This has resulted in several F-line boarding islands too narrow for today’s standards under the Americans With Disabilities Act. While these stops are technically ‘grandfathered,’ Market Street Railway supports the concept of full accessibility for the F-line, with ramps at every stop.

Stop realignment on Market Street opens possibilities for exciting concepts. One such was advanced by Laubscher during a recent stakeholder design input meeting involving the block of Market between Fourth and Fifth Streets, where high pedestrian and transit rider volumes make it hard to accommodate all users. Since all in the group believed that autos should be completely banned from this block, Laubscher proposed combining the Fourth and Fifth Street F-line stops in both directions into a station midway between, at Powell Street. The station would provide an easy-to-identify F-line connection for both visitors and residents. Its placement adjacent to the Powell cable car turntable would make it easier for Muni workers in the Hallidie Plaza ticket booth to direct questioners to the F-line stop.

Under the current six stop proposal, all downtown ‘island stops’ (those used by the F-line, located in the center or track lanes of Market), would be shared by the historic streetcars and two or three long-distance Muni bus lines that run to far edges of the city, such as the 9-San Bruno or 71-Haight-Noriega. The idea is to provide what amounts to limited stop service on Market for riders who have already come a long way on their Muni vehicle, thus shortening their trip somewhat.

Tickets, please

Critical to the success of this stop consolidation effort, in Market Street Railway’s view, is complete prepaid boarding on downtown Market Street island stops. Muni recently extended ‘Proof of Payment’ to lines including the F, whereby riders with Clipper Cards (prepaid fare cars that supplanted the Fast Pass), Visitor Passports, or valid transfers can board via the vehicle’s rear door. Prepaid boarding would require ticket machines at each stop, as are very common in Europe, and require all riders to have their fare paid before boarding F-line cars downtown.

This would greatly reduce ‘dwell time’ at downtown stops. Today, F-line streetcars can take three or more minutes to make a single stop, as confused visitors question the operator, fumble with dollar bills to feed the outmoded vehicle fareboxes, and ask for change that operators don’t carry. Clear, multilingual signage is critical for the success of such a program, so Market Street Railway has volunteered to help Muni create clear and concise instructions to intending F-line riders. (Market Street Railway also advocates prepaid boarding at other busy stops such as the Ferry Building, Pier 39, and the Wharf terminal.)

From our nonprofit’s point of view, this mix of fewer stops and faster boarding on Market is essential for the F-line to continue to accommodate projected ridership growth, which we estimate now approaches 25,000 daily. Currently, automobiles using the track lane between Sixth and Steuart on Market often keep the streetcars from reaching the boarding islands promptly. That, plus the current slow boarding process outlined above, means streetcars can take two or even three signal cycles to get past a congested intersection.

Making these changes would bring the performance of the F-line on Market closer to the quick trip along the Embarcadero north of the Ferry Building. Those changes would extract more value from these priceless vintage vehicles by carrying more riders more efficiently, with less stress on operators, who have one of the toughest jobs at Muni.

Needed: A short turn loop

Spend some time riding end to end on the F-line and you’ll discern that it’s really at least two lines in one. The western end of the line, from Castro to Downtown, functions much like a neighborhood trolley, as mentioned above. Residents of Upper Market and adjacent neighborhoods frequently choose the F-line over the crowded and sometimes unreliable Muni Metro subway underneath. And when the subway suffers a serious snarl, the F-line is essential to get these residents to and from work.

This part of the line is also seeing explosive residential growth. Several thousand new housing units are currently under construction along Market Street between Noe and Seventh Streets, with many more planned. Under city zoning regulations, most of these buildings offer fewer than one parking space per unit, which will make many of these new residents transit-dependent.

On top of that, mid-Market (between Van Ness Avenue and Fifth Street) finally seems to have turned the corner toward the full-blown renaissance that many San Franciscans have waited half a century to see. Hot tech companies like Twitter, Square, and others have taken space along this stretch of Market, bringing in a mostly-young workforce that prefers bicycling or riding transit to driving. All this will drive even more commute-hour demand for F-line service in this corridor.

In contrast, from Fifth Street to Fisherman’s Wharf, F-line demand comes from a mix of recreational riders (mostly visitors) and locals, including a lot of Wharf employees. Their riding habits make the most congested times on this segment of the F from about 10:00am through 10:00pm, seven days a week, a different mix than the western end of the line.

Over the years since the F-line opened, Muni has tried to address this demand disparity with additional ‘short turn’ service from the Wharf to turnaround points short of Castro. The problem is that there are only two spots where single-end streetcars (about 80% of the active fleet) can reverse: the loop around our San Francisco Railway Museum on Steuart Street and Mission, and the ‘wye’ stub-end turnaround at Eleventh and Market, just short of Van Ness.

Dropping shuttle riders coming from the Wharf at the Ferry loop, as is now done, doesn’t work well, because many want to go on to the Union Square area. Taking them onward along Market, as Muni has tried several times with its F-line shuttles, requires the cars to run seven blocks past Union Square to reverse on a street, Eleventh, that used to be quiet but is now crowded with auto traffic turning off Market plus the articulated buses of the 9-line. The streetcar turnaround process at Eleventh is now very slow.

All this growth along Market Street, which the F-line itself has facilitated, requires more flexibility in managing the line today, specifically more options for turning cars back. Market Street Railway strongly supports installing a streetcar turning loop using McAllister Street and Charles Brenham Place (the short extension of Seventh Street on the north side of Market). This compact loop, to reverse streetcars headed westbound on Market, requires far less track laying than any loop going south of Market, and would have an easy half-right turn from Market, rather than a left turn across oncoming streetcars required by a south-of-Market loop. A north curb lane alignment would allow it to make the sharp turn onto Charles Brenham’s west curb lane. Overhead poles and feeders already exist on McAllister, for the 5-line trolley coaches, and there is room for streetcars to lay over on Charles Brenham, adjacent to UN Plaza.

This option would allow for augmented short turn F-line service from the Wharf that reaches not only Powell Street, but mid-Market and the edge of Civic Center as well. At a minimum, a compact loop of this type provides Muni inspectors a powerful tool for rebalancing the line after blockages.

So far, So good

In our discussions with top SFMTA officials, we’ve received positive feedback on our priorities for Market Street’s future. They agree on pre-paid boarding, stop spacing, the cycletrack, and the short-turn loop. However, other City agencies must agree as well, and, as we have outlined here, some seem to have differing priorities. We will keep you up to date on the planning process for a 21st century Market Street, and at the appropriate time alert you to ways you can help us achieve the maximum benefit to Muni riders along our city’s ‘grand promenade’.