During the first weeks of 1915, Pancho Villa proclaimed himself in charge of Mexico. Germany began open submarine warfare in the Atlantic as the Lusitania prepared to sail to England. California’s only active volcano, Mount Lassen, was erupting–spewing ash for hours at a time. And as bad weather pelted San Francisco, workmen toiled ’round-the-clock on the city’s northern shoreline to complete preparations for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE). Initially conceived in 1904 to occur upon the completion of the Panama Canal, this event had become a celebration of the rebirth of San Francisco following the devastating Earthquake and Fire of 1906. Millions of dollars went to develop the site and to promote San Francisco as the host city. When San Francisco was selected for the Fair over New Orleans, President William Howard Taft stated, “San Francisco knows how.”

Indeed, San Franciscans had much to be proud of. They had used one of the worst natural disasters on record as the springboard for a number of civic improvements, including the new City Hall and Municipal Auditorium. Another civic improvement would prove to make all the difference in getting crowds to the Fair. This was the launching of the Municipal Railway of San Francisco (Muni)–an ambitious experiment in street railway ownership, construction, and operation. The Railway began operations December 28, 1912 with just ten cars on Geary Street. Yet just twenty-six months later as the exposition opened, Muni was operating almost 200 streetcars over ten lines, and had vaulted into a much stronger competitive position against its dominant private rival, United Railroads.

The site

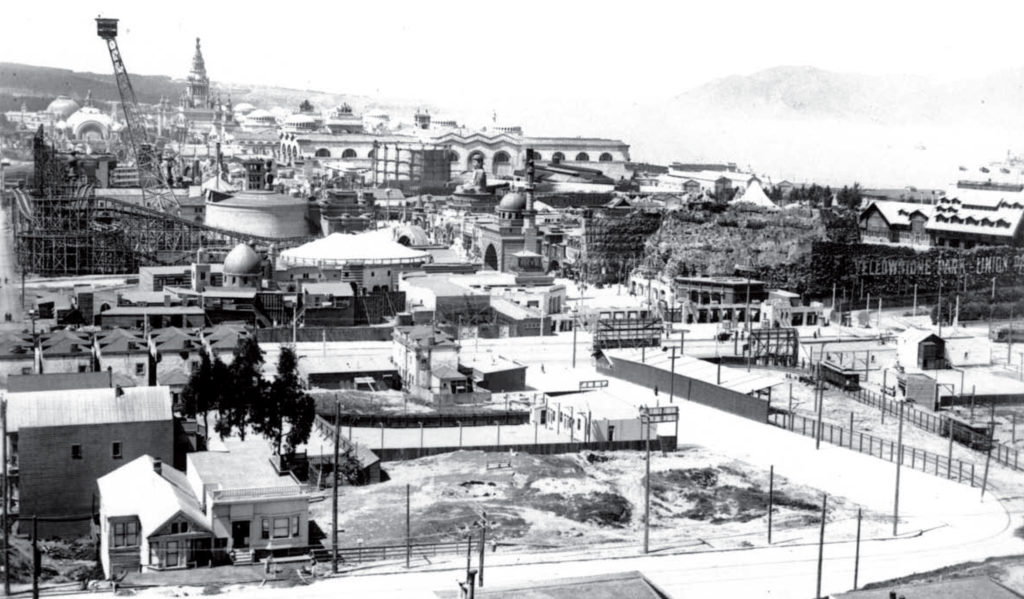

PPIE construction commenced in 1912 on 635 acres in an area called “Harbor View”, extending from Van Ness Avenue almost to Fort Point. The site, later known as the Marina District, was cobbled together from a piece of the Army’s Presidio, a stalled real estate development, and land reclaimed from San Francisco Bay. It was a long way from downtown hotels and other neighborhoods. To succeed in an era totally reliant on public transportation, there had to be an efficient and reliable way to move crowds of people to and from the Fair.

This posed several significant challenges that had to be overcome by the city’s street railway system during the scheduled 288-day run. In light of this, the Board of Supervisors engaged Transit Consultant Bion J. Arnold to make suggestions “in order to improve the transportation facilities of this city.” Arnold described the existing lines’ inadequate capacities to transport people to the PPIE. He stated that the only “important line” that “reasonably approaches” the Exposition site was the Polk Street line of the United Railroads with a capacity of 12,000 passengers per day. The Union Street electric line of Presidio & Ferries Railroad could carry 4,800 passengers per day, while California Cable Railroad’s Hyde Cable Line and the United Railroads’ Fillmore Line together only had a capacity of an additional 9,300. He noted, however, that the Polk line’s terminal was a mile from the main exhibits and two miles from the sports and drill grounds.

The plan

In response, the Board of Supervisors turned to City Engineer M.M. O’Shaughnessy to provide a plan and estimate of cost of a “Municipal System of Street Railways…designed to furnish to the Panama-Pacific Exposition a fully adequate street railway service…” While outlining several route options, O’Shaughnessy indicated that the Exposition was expected to draw as many as 8,640,000 visitors overall and stressed that, on the day of maximum attendance, a total of a quarter-million persons were expected. Many of these would arrive from points east at the Ferry Building or come from the Peninsula and points south via the Southern Pacific Railroad.

Motor vehicle alternatives

While automobiles were not considered to be a primary form of transportation, there were options to reach the Exposition, including the new competition of nickel jitneys and open-buses mounted on early truck chassis. Bus routes were to operate to the gates, and the Arnold Report warned, “If adequate street railway facilities are not available, motor buses will have to be relied upon for a considerable share of land traffic.” Unfourtunately, the buses of that time were rather precarious devices of limited seating capacity.

The street railway system

Given the size of expected crowds, very limited private automobile ownership, and the state of bus development, it was clear that streetcars would be the primary means of serving the 1915 Exposition. Both Muni and URR would respond by establishing new terminals, routes and (in the case of Muni) new lines.

United Railroads lines & routes

With its strong philosophical and political support of the nascent Municipal Railway, the city had become increasingly combative with rival United Railroads over its franchise rights on city streets. In this environment, URR indicated it was unwilling to build track extensions to serve the Fair.

The URR’s regular 19-Polk line offered service from Ninth and Bryant via Larkin and Polk to the PPIE Van Ness Avenue Entrance. URR also adjusted the route of the 23-line (Fillmore-Valencia) from its terminal at Sacramento and Divisadero to Fillmore and Broadway, to connect with its existing counterbalance on Fillmore Hill. Four new routes on existing trackage provided service to the Fair from the Southern Pacific Depot, Mission District, Ferry and the Haight. United Railroads did build a few feet of new trackage, in the form of a temporary loop at the north end of its 19-line, and assigned three new routes to it, augmenting the 19: the 32-Depot-Exposition, from the Southern Pacific depot via Townsend, 4th, Ellis, Hyde, O’Farrell, Larkin, Post and Polk Streets (returning via Polk, Post, Larkin, Ellis and Fourth); the 33-Mission-Exposition, from 29th and Mission via Mission, 9th Street, Larkin, Post, and Polk; and the 34 Sutter-Exposition, which ran from the Ferry Building via Market, Sutter, and Polk. Additionally, the 35-Haight-Exposition line operated from Carl and Stanyan via Carl, Clayton, Frederick, Masonic, and Page to Fillmore, returning via Oak Street. It allowed transfer to the URR Fillmore lines 22 and 23, which in turn connected with the Fillmore Hill counterbalance line to reach the Fair. [Note that after the Fair, the numbers of these temporary lines were reassigned to newer lines.]

Most of the URR routes only reached the eastern edge of the Fair, the so-called ‘Fun Zone’–far away from the main exhibitions. The only URR line directly serving the main area was the Fillmore Hill line, which operated over Fillmore Street’s 25-degree grade from Broadway to Green by use of an ingenious counterbalance system. Tiny, single truck electric streetcars (twins of preserved ‘Dinky’ No. 578s) were secured by a “wishbone” to a fixed grip “plow” connected to an underground cable at the top and bottom of the hill simultaneously. The northbound car descended the grade (with power on); its weight helping pull the southbound car up the hill. Attempting to meet traffic demands, the URR closed the formerly open cars and coupled them in pairs, with the lead car receiving power and feeding it through its controller to the two motors on each car using connecting cables. The public must have expressed some trepidation about the ominous Fillmore Hill grade. Despite installing a stronger cable and newer connecting “plows”, the URR felt compelled to note in its revitalized April 1915 Transit Tidings service brochure that “the Fillmore Hill Line is absolutely safe.” In fact, given the overview of the Exposition site from atop Fillmore Hill, the line may have also been one of the more exciting rides of the entire PPIE experience.

New municipal railway: Lines and routes

In light of O’Shaughnessy’s recommendations and the fact that the URR would not be building new lines, the Board of Supervisors augmented the existing Municipal Railway Geary Street lines by approving the creation of three new Muni lines and purchasing a fourth, all with the immediate purpose of serving Fairgoers. These four lines went on to serve San Franciscans beyond World War II with streetcars, and with some changes, they still carry Muni riders, albeit with buses. During the Exposition, though, these lines sometimes served terminals different from their later ones.

When the franchise of the Presidio and Ferries Railroad’s Union Street line expired in December 1913, the City bought it, rebuilt it to Muni standards, and renamed it the “E-Union”. It ran from the north Ferry terminal on The Embarcadero through the Produce District on the one-way pair of Washington (outbound) and Jackson (inbound) Streets, then over Columbus Avenue to Union, and over Russian Hill via Union, Larkin, and Vallejo Streets, then jogged on Franklin to reach Union, which it followed to the Presidio. It served the Baker Street and Presidio entrances to the PPIE. The D-Van Ness began operating on August 15, 1914, from the Ferry via Market, Geary, and Van Ness, until it reached the E-line trackage at Vallejo. From that point, alternate cars provided service in both directions on the “Exposition Loop” formed by tracks on Union, Steiner, Greenwich, and Scott to Chestnut Street. After the Fair closed, the route operated both directions on Union, Steiner, Greenwich, and Scott to a crossover installed on Chestnut Street. Later, on May 4, 1918 after new tracks were installed on three blocks of Greenwich from Steiner to Baker Street, the D-line joined the E in serving the Presidio, utilizing a unique route following Steiner and Greenwich to avoid the steep grades on outer Union. The “mountain goat” single truck cars of the E could navigate grades that the double-truck cars of the D could not handle.

On August 15, 1914, the H-Potrero began offering cross-town service from 25th Street and Potrero Avenue via Potrero, Division, 11th Street, Van Ness Avenue to Bay Street. Upon completion of a right-of-way through the ‘upper post’ of the Army’s Fort Mason. It was extended to a loop on Laguna Street on December 29, 1914. Supplemental services were also offered over H-line track to the Chestnut loop from both Sixteenth and Potrero and from Market Street. The F-Stockton was inaugurated on December 29, 1914 from Market and Stockton Streets via Stockton, through a new tunnel drilled between Union Square and Chinatown, then via Columbus, North Point, and Van Ness before it reached its terminal at the Fort Mason Loop. After the Fair, it was re-routed on Van Ness and out Chestnut to Scott. Muni showed flexibility during tthe Fair in adapting to Fairgoers’ travel patterns. Three additional Muni routes were established specifically for the Fair.

A new “G” (Columbus Line) operated from Stockton and Market over parts of the Presidio and Ferries Union Street Line via Stockton, Union, Larkin, Vallejo, Franklin, Baker, and Greenwich to the Presidio & Ferries terminal in the Presidio. An “I” line ran from 33rd and Geary to the Exposition Loop via Geary and Van Ness, making the same loop as the D. Municipal Railway Operating Revenue Logs for FY 1914-15 reveal that, in addition to the first three days of the Fair, it ran on Sundays and holidays, and a few Saturdays, at least through July, 1915. Despite infrequent operation, it generated considerable revenues per day. A “J” route (not to be confused with the current J-Church) began operations on February 10, 1915, sharing E-line trackage from the Ferry to Columbus and Union, then F-line tracks to Van Ness and the Fort Mason Loop. On July 9, 1915, it was re-routed up Van Ness and out Chestnut to Scott. Beyond these regular dedicated exposition lines, there is evidence that both Muni and URR diverted service from other lines to the Exposition on particularly heavy demand days. But even when on their normal routes, URR cars operating on the Market, Haight and Sutter Street lines regularly bore “Exposition via Polk St. or Fillmore St.” dash signs to encourage transfer to URR Fair routes.

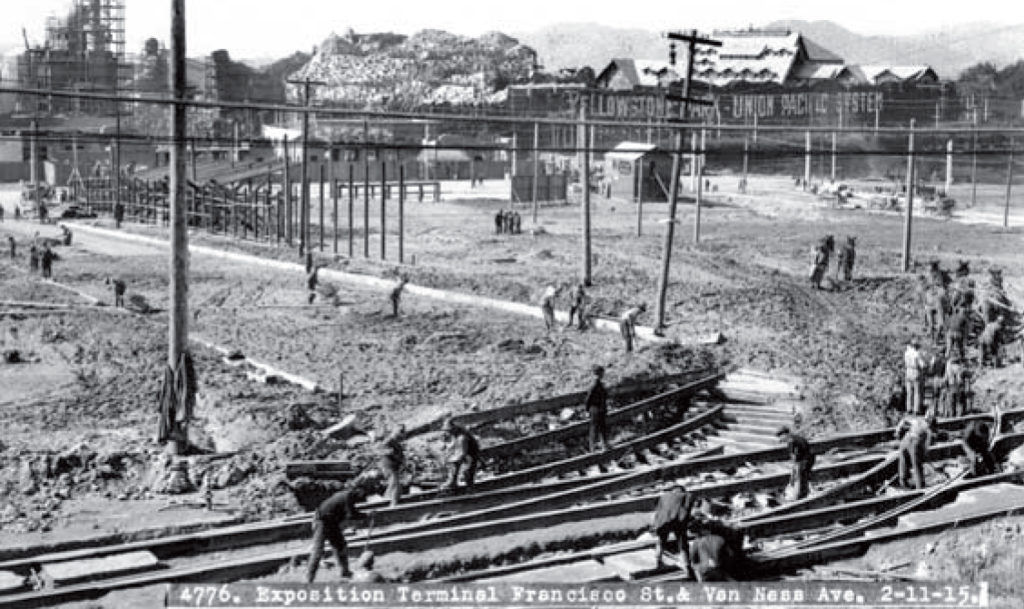

Terminals

Both URR and Muni installed high-capacity loop terminals to disgorge and load crowds rapidly at various Fair entrances. To expedite car loading at the Fort Mason Loop, Muni constructed an enclosed temporary station to allow for change making and prepaid boarding of cars. The United Railroads also constructed a loop and high-capacity loading shed on a block of land it owned bordered by Francisco, Polk, Bay, and Van Ness Avenues (now occupied by Galileo Academy of Science and Technology).

Success by any measure

The Panama Pacific Exposition was a success in all respects. By the time that the last turnstile had turned, 18,876,438 admissions had been recorded, ten million more than the planning estimates, showing that many people came back again and again. Average daily attendance of 65,543 more than doubled the estimate of 30,000. Although planners estimated the highest attendance day of the PPIE would draw about 250,000 people, the closing day crowd was 459,022 (almost equal to the city’s population of 485,000). Undoubtedly, the efforts of San Francisco’s transportation services contributed to the Fair’s success. Both the United Railroads and Muni enjoyed windfall profits from this service as did the Ferry services of both the Key Route and Northwestern Pacific.

Legacy

The nascent Municipal Railway met the construction and operational challenges of the Exposition while acquiring 125 “B-type” cars that would be the backbone of its fleet for the next forty years. Although construction delays on Muni’s “A” and “B” lines along Geary Street raised skepticism, all construction and car deliveries for the Fair were completed ahead of schedule. Throughout the PPIE, the fledgling Muni management staff also gained considerable operational experience in meeting varied service demands.

San Franciscans today often cite the Palace of Fine Arts as the only surviving remnant of the PPIE, but there are in fact several others. The Auditorium at Civic Center (now named for Bill Graham) was constructed by the PPIE and presented as a gift to the city. The Stockton Tunnel was built so the original F-line could serve the Fair, and the Fort Mason Tunnel was built for freight railroad service to help build the Fair. (It later served the Army, and is now being studied as an extension of the latest E-line–the E-Embarcadero–to reach Fort Mason from Fisherman’s Wharf.) The Broadway Tunnel, while not built until 1952, was originally proposed to provide access to the Harbor View area for the PPIE. However, the main legacy for Muni was a well-built system connecting the northeastern and north central portions of the city to the Ferry Terminal as well as the financial and retail areas. When the Fair closed, Muni service along the D, E, and F lines fostered the residential developments and retail streets that became known as the northern portion of Cow Hollow and the Marina District. In the end, the city was left with the route structure upon which streetcars would operate for the next 35 years. Most importantly, by meeting the challenges presented by the Exposition, Muni demonstrated that it was a vital and mature agency of the “City that Knows How”.