The 6-Haight-Parnassus trolley coach line returned to service July 9, 2022, after being shut down since the start of the Covid pandemic in Spring 2020. We recounted the history of this line in our exclusive member magazine, Inside Track, in 2019. We hope readers who enjoy this story will join us or donate, so we can keep telling stories like this.

Enjoy your trip on the 6, and the great view at the end of the line!

By Rick Laubscher, Market Street Railway President

If you wanted to “get high” on rail transit in San Francisco during the first half of the 20th century, not even the cable cars got you as high as the 6-line streetcar. As the second half of the century opened, it got even higher, as a trolley bus line. The history of the 6-line is literally a long and winding road. It started in the wake of tragedy.

Quick background: Before the 1906 Earthquake and Fire, United Railroads, the dominant private transit company of the day, had been prohibited from erecting overhead wires on Market Street. City officials, pressured by citizens who hated the idea of wires on their main street, required the continued use of cable cars on Market, even after they had been replaced by faster, larger electric streetcars on flat routes in city after city. United Railroads did operate numerous electric streetcar lines, but the rules generally limited them to crosstown and South of Market lines.

After the shaking and burning ended in April 1906, though, United Railroads won permission to scrap the five cable car lines that radiated from Market Street and replace them with electric streetcars. They electrified those five lines immediately (except the Castro Street hill trackage, which remained cable until 1941).

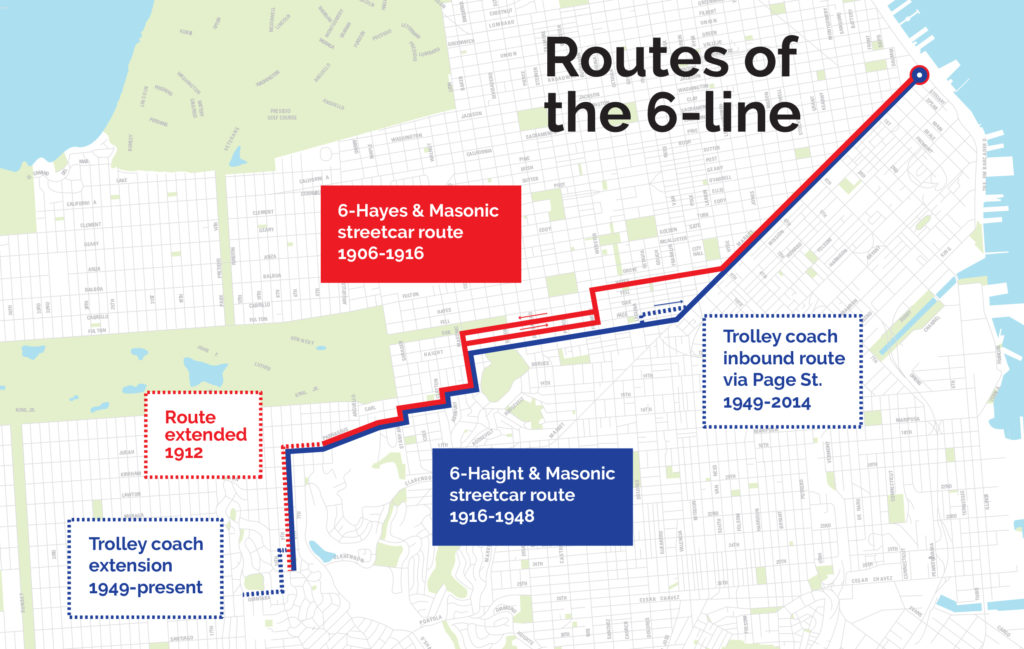

But United Railroads wanted to add more streetcar lines radiating off Market, the busiest street in the city, and quickly pieced together a new line running from the Ferry Building out Market via Hayes Street (on the existing standard gauge cable car tracks with wires strung overhead), to Fillmore, and then over tracks of existing streetcar lines via Fillmore, Oak (returning on Page) and Masonic, zigzagging along Frederick, Clayton, Carl, and Stanyan streets to avoid too-steep grades, and then along Parnassus Avenue to the “Affiliated Colleges” (now UCSF) at Third Avenue. Amazingly, this new line opened to streetcar riders barely seven weeks after the earthquake on June 10, 1906. This line was initially called the Hayes-Masonic.

By 1912, streetcar lines had been assigned numbers. What was now called the 6-Hayes-Masonic was extended that same year on new tracks westward down the hill on Parnassus (which becomes Judah Street) to Ninth Avenue, then south up another steep (for a streetcar) hill to reach Ninth Avenue and Pacheco Street, the edge of the then-new fancy residential district called Forest Hill. This was the highest point ever reached by a San Francisco rail line (including cable cars!).

On February 7, 1916, the inner portion of the 6-line was rerouted to run via Haight from Market to Masonic, making the line more direct and providing more streetcars on inner Haight, where there were more prospective passengers than Hayes, which already had the 21-line. Thus was born the six mile long 6-Haight & Masonic line, which runs the same route (slightly extended, and with trolley buses) more than a century later. It’s now called the 6-Haight-Parnassus.

Sixes and sevens

Operationally, the 6-line ran by itself for its westernmost 2.3 miles, but shared its route on Haight and Market Streets with the 7-Haight & Ocean and 17-Haight & Ingleside lines. In those days, the 7-line continued westward on Haight from the 6-line’s turnoff at Masonic to skirt the south edge of Golden Gate Park on Lincoln Way all the way to Ocean Beach, and then jogged north to terminate at Playland. The 17-line stayed with the 7 on as far west as 20th Avenue, then ran south through the Sunset District to Sloat Boulevard, never really reaching what’s now thought of as the Ingleside District.

Back when the 6-line opened, the Sunset District promised rapid future residential growth, and the Inner Sunset, where the 6-line ran, understandably grew first because of the shorter trip time downtown. The 7- and 17-lines quickly faced fierce competition from the nascent Municipal Railway. Muni’s L-Taraval line opened in 1919, and was soon routed through the new Twin Peaks Tunnel for a faster trip downtown, sucking riders from the 17. In 1928, Muni’s N-Judah line opened through the new Sunset Tunnel under Buena Vista Park, sapping ridership from the 7-line, which paralleled the N two blocks north.

Even before the N-line opened, though, the 7- and 17-lines were losing money (when measured against a desired 7% return on investment). However, the 6-line was profitable on that basis when measured in 1926, in part because it faced less competition from Muni on the outer end of the line. (The Forest Hill Station of the Twin Peaks Tunnel was a half mile from the end of the 6-line’s streetcar tracks at Ninth Avenue and Pacheco, down a steep hill.)

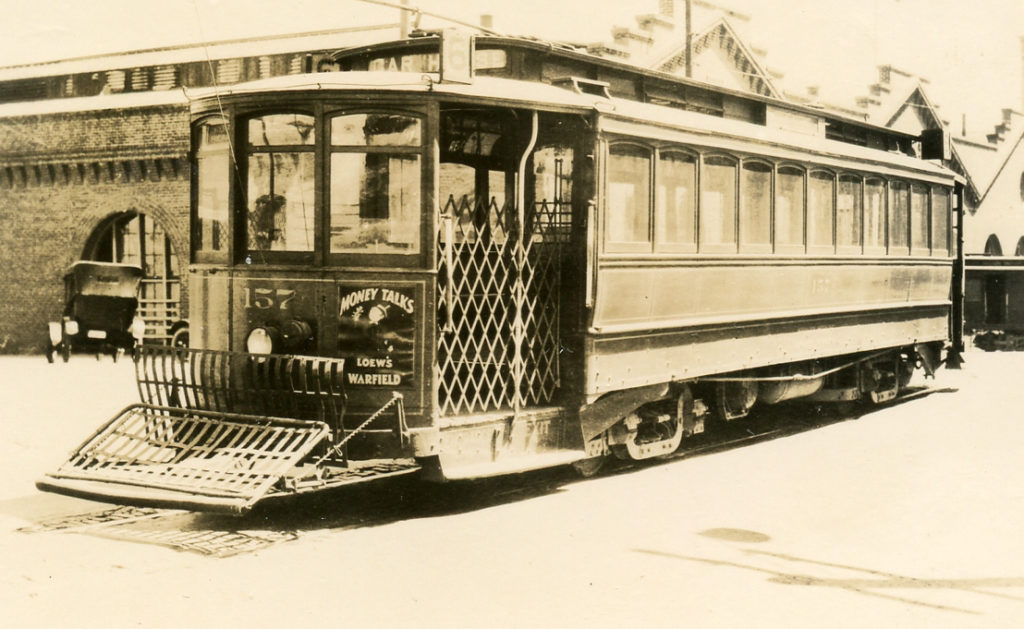

Though they shared operations on Haight Street, the 6-line’s streetcars were housed in a different place: the imposing brick car house at Oak and Broderick Streets, rather than the wooden barn at Haight near Stanyan, which housed the 7- and 17-lines, along with the 33-Ashbury. Still, the 6, 7, and 17 all usually used the same type of streetcar: the “100s.” This class of 80 streetcars, named for their fleet numbers, were purchased new in 1911 from the Jewett Car Company of Ohio, the same manufacturer who three years later built 125 streetcars to fuel competitor Muni’s rapid expansion.

Originally, these streetcars were not very popular with the public. The windows didn’t open, making the car uncomfortable on hot days. The seats were longitudinal benches, putting riders with their backs to the wall. And, horrors, there was only a single section to the car, meaning no separate space for people to smoke! In 1927, though, Market Street Railway began an upgrade program on the 100s, replacing the benches with leather-upholstered cross seating, adding windows that opened, and creating a separate smoking section inside the car. Riders liked them better after that. (None of this streetcar class survived, but our volunteers crafted a faithful replica of the end of “Car 105”, which forms the centerpiece of our San Francisco Railway Museum.)

Sharing with the N

Market Street Railway and Muni were fierce competitors back in the day. Each had its own fares and transfers. If you wanted to switch from, say, a 6-line streetcar to an N-Judah, you had to pay a separate fare. Even when the fare was just five cents, that mattered to many San Franciscans.

The 6-line and the N-Judah had an unusual relationship. When Muni decided to dig the Sunset Tunnel in the 1920s, the logical west portal was near Carl and Cole Streets in what’s now called Cole Valley. But the 6-line already had the franchise for that part of Carl Street. So an arrangement was made under which Muni paid “rent” for the two blocks of joint trackage on Carl between Cole and Stanyan Streets, where the 6-line turned south to reach Parnassus. This shared stretch of track was unavoidable, but Muni preferred its own right of way wherever possible, and so routed the new N-line westward on Carl Street and Irving Street before turning south for a block on Ninth Avenue to reach Judah and the rest of its westward journey. This left the two lines running just a block apart for almost a mile, albeit with the 6 running on a much higher elevation along the flank of Mount Sutro on Parnassus.

Muni takes over

Starting as early as 1925, the city tried repeatedly to buy out Market Street Railway, but voters rejected the purchase several times, apparently opposed to issuing city bonds to pay for it. In 1943, the campaign for the last bond-issue related attempt promoted running the 6-line through the Sunset Tunnel along with the N for faster service. That attempt was narrowly defeated. The next year, newly elected Mayor Roger Lapham offered a different plan that didn’t require issuing bonds. It passed, and on September 29, 1944, the 6-line, like the rest of Market Street Railway, became part of Muni. However, Lapham’s plan contained a restrictive provision prohibiting Muni from making major changes to the former Market Street Railway operations until the purchase price was paid off. The 6-line cars were already sharing track with the N-line right up to the tunnel portal, but this restriction kept them from immediately operating through the tunnel.

Before the purchase of Market Street Railway was paid off through a bond issue approved by voters in 1947, the city retained a consultant, former Market Street Railway Vice President Leonard Newton, to prepare a comprehensive plan for rationalizing the routes of the two properties. Newton’s plan recommended retaining fourteen radial streetcar lines. Rather than putting the 6 into the Sunset Tunnel, though, Newton recommended the 7-line for that speeded-up operation. The 7 would have run via the N-line from the Ferry through the tunnel to Ninth and Irving, then would have turned north a block on Ninth to reach Lincoln Way and follow its old route to Ocean Beach. The 17-line would have stayed on Haight as a streetcar but would have terminated at 20th Avenue and Lincoln Way, eliminating the cross-Sunset operation.

The 6-line did not make Newton’s cut of recommended streetcar lines to be saved. (Newton’s complete 1946 list of recommended retained streetcar lines: B, C, F, H, K, L, M, N, 3, 4, 7, 17 [inner portion], and the 40-San Mateo interurban.)

Despite Newton’s recommendations (which included buying 313 PCC streetcars!), Muni decided to move in a different direction. The streetcar infrastructure inherited from Market Street Railway was dilapidated; automobiles were jousting for space on what had previously been primarily streetcar streets, and the city generated “free” electricity from its Hetch Hetchy project in the Sierra Nevada. For these reasons, Muni made the decision to minimize its streetcar mileage, and invest instead in an extensive trolley coach network. The 6-line was a beneficiary of this decision.

Extending the 6

Muni inherited one trolley coach line, the 33-Ashbury, converted by Market Street Railway from streetcar operation in 1935, and had started one of its own, the R-Howard, in 1941 (later extended over the E-Union streetcar line and redubbed the 41-Union-Howard). The big expansion would require a new trolley coach facility, Presidio Division, behind Muni’s Geary streetcar division, and conversion of its Potrero streetcar facility for trolley coaches. The 6-line would run out of Potrero (and still does).

On July 3, 1948, streetcar service on the 6-Haight & Masonic ended, replaced at first by motor coaches while overhead wires were modified, and then, exactly one year later, by brand new trolley coaches on an extended route. Since the 6-line streetcars used a stub-end terminal, a trolley bus loop had to be built anyway. Surveying the surrounding streets, Muni decided to climb higher and go west into the newly developing neighborhood of Sunset Heights (which in those days especially would have been more appropriately named Foggy Heights). So, the block of the streetcar route between Ortega and Pacheco on Ninth Avenue was abandoned, with the trolley coach extension using Ortega, climbing a block too steep for streetcars, then turning south on Tenth Avenue for two blocks, and then westward on Quintara Street to a literal cliff at 14th Avenue, where a tight terminal loop was built, still in use today.

The author lived on Quintara near 12th Avenue as a young boy and fondly remembers the big trolley coaches lumbering back and forth on the narrow residential street. While Muni had purchased three makes of trolley coaches, the Marmon-Herrington buses (including preserved Coach 776) almost always worked the 6.

During the trolley coach era, which has now lasted almost twice as long as the streetcar era did, there have been only two route changes. For some reason, the city made the first few blocks of Haight Street one-way westbound when the conversion occurred in 1949, forcing inbound Haight lines (which also included the 71 and 72 motor coach routes for decades) to jog north to Page Street at Laguna. In 2014, SFTMA, now in control of the streets themselves as well as of Muni, reversed that change, creating an exclusive eastbound lane for buses on those blocks of Haight to speed service, thus restoring the streetcar-era routing. Also, for some years, the 6-line trolley coaches terminated at the old East Bay Terminal at First and Mission Streets, instead of the Ferry. More recently, though, the eastern 6-line terminal was moved back to the Ferry Building, and in fact, 6-line coaches lay over today right next to our San Francisco Railway Museum on Steuart Street!

An additional proposed extension of the 6-line has come up short, at least so far. When the outer terminal was built, 14th Avenue did not extend south from Quintara. A steep street was later built, and Muni proposed using it to extend the line to West Portal, giving riders on the outer end of the 6-line access to the K, L, and M lines in the subway. But neighbors on 14th Avenue bristled at the thought of overhead wires on their block and scuttled the proposal.

A line to love

The combination of Market Street operation, the historic residential and commercial corridor of Haight Street, and the meandering route through narrow streets of the Inner Sunset, capped with a terminal seemingly at the top of the city, all served by electric trolley coaches, makes the 6 a line we love!

If you like our exclusive content, please consider even a small donation to help our nonprofit.

Thanks for the great history of the Number line and the photos that appear.

Fascinating and informative presentation.

Thank You, Mt. Laubscher for your painstaking accounts of San Francisco public transit heritage. Getting as old as I am is not all fun; remembering SF electric and steam railway experiences going back to the end of WWII is… My one ride on the Key across the bridge was forced by missing the last ferry run of the night in April 1957; we had to catch the train to Sacramento. Got off at 14th & Adeline -I think.- Climbed Freeway chain link fences to get to the Oakland SP depot on time… Jesus love me more than I know!

Earlier, on that Easter week trip we saw the SP 4-8-4 #4443 being primped for cameo in the Sinatra Movie “Pal Joey.”.. See the Alco SF Port RR Diesel run by the Ferry Building sidewalk in that. 1957 movie- just a glimpse from inside the Ferry Building, look sharp!

Near end of WWII we recall night ride across the Ferry Building pedestrian ramp. Any Embarcadero ramp stories here? Probably in my stroller’

As a toddler one actually does remember some standout events, like a WP 481 class on the 19th Street “Wye” in Sacramento, and being scolded for pulling the partition door closed on a Sacrament0 35-40 series California Car (American Car Co. 1913/1914]. Any pictures 1914 CA State Fair 6 California Car line-up?

Stay well Rick

Hi Rick: I looked at the pictures in the article on the No. 6 Line and I will read the article after I send this. I lived in SF the first 5 years of my life. My mom and dad did not drive, so we had to take the street car to wherever we wanted to go.. Iwas born at UC Hospital on Parnassus Ave and I lived at 806 Guerrero St. so we rode the 10 Bus and the 6 car to the hospital for my chjeckups. My mom had a lady friend who lived on Haight St., so we rode whatever car that may have come along.

Years later, I just happened to be driving near the end of the 6 Line on Quintara Street and it downed on me that someone could ride the 6 Bus to the end of the line and walk to 15th and Taraval and catch the L Train to either end of the line.. Thanks for letting me tell you my story.

Really Nice Post!

Wonderful news – the 6 line is back in the land of the living!

As a child I was a regular 6 line rider in the 1940’s as we lived at 11th & Pacheco. The photos of the streetcars bring back fond memories. All they need to be complete is my smiling face looking out of the left front window.