Third of six installments in our history of Muni’s birth and first century

As San Franciscans celebrated Thanksgiving in 1941, many were thankful that the economy was finally climbing out of the decade-long Depression that had savaged the city. The downtown area had hardly changed since three high rises had framed the boundaries of the district: the 26 story Pacific Telephone Building at 140 New Montgomery Street in 1925; the 32-story Russ Building, the city’s tallest, which opened at 235 Montgomery Street (the self-proclaimed ‘Wall Street of the West’) in 1927; and the 28-story William Taylor Hotel (now a Hastings Law School dorm) at 100 McAllister Street, in 1930.

The city’s transit showed little change as well. Four streetcar tracks still ran the length of Market Street, the outer pair for the publicly owned Municipal Railway (Muni), the inside tracks used by its private competitor, Market Street Railway Co. (MSRy, our nonprofit’s namesake). There had been attempts to consolidate the two systems, but voters turned thumbs down every time. Other than five streamlined faux-PCC streetcars purchased in 1939, Muni’s streetcar fleet had not been augmented since 1927, though it had bought its first trolley buses (for a Howard Street line that replaced MSRy streetcars) and expanded its motor coach fleet to inaugurate some crosstown services.

As it turned out, Muni would need every single vehicle in its fleet to meet the tidal wave of riders that was soon to descend on it, even as its competitor left scores of its own streetcars sidelined.

Adapting to war

San Franciscans, like the rest of the nation, were jarred on that sleepy Sunday, December 7, by the shocking news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Some panicked, believing the fleet of the Rising Sun could be headed toward them. Indeed, Japanese submarines soon prowled the Pacific coast. So, preventive measures were taken, such as a net stretched across the Golden Gate to keep them out of the Bay, manning of the existing coastal gun emplacements, and a blackout along the western side of San Francisco.

The blackout included streetcars. In an article republished in the Winter 1997 issue of our nonprofit’s member magazine, Inside Track, George U. Janes remembered a westward night ride on MSRy’s 31-Balboa ‘high speed’ line, roaring through the Avenues with lights ablaze until reaching Park-Presidio Boulevard.

The motorman reaches up and one by one snaps switches, and car lights…extinguish. The entire car is in total darkness. And so is the heavily traveled intersection. And so is Balboa Street all the way to the ocean. Everything out there blacked out and a thick fog to boot—the whole place is like a Hollywood movie set for a mystery film… The blacked-out 31 races through pitch-black intersections at full speed, bell clanging furiously. Nobody, least of all the motorman, can see a thing. ‘They haven’t allowed any additional running time,’ he remarks. ‘Good thing we are on rails.’

George U. Janes

It was a good thing all of San Francisco was on rails back then. Its streetcars, and the people who ran and maintained them, played an essential role in the war effort.

Almost immediately after Pearl Harbor, Muni and MSRy began running preparedness drills at their storage and maintenance facilities to be ready for the worst. MSRy moved buses out of its barn at 24th and Utah Streets, figuring they’d be less susceptible to bomb damage in the open than in the building.

The blackouts soon gave way to longer-lasting and higher-impact war measures. Fuel and tire rationing was near the top of the list. Suddenly, the private automobile was a burden, not a blessing, for workers and families. And they turned to transit.

Muni already served most existing defense facilities in the city. The H-Potrero line ran right through Fort Mason, terminating at the Port of Embarkation for Pacific-bound troops. The F-Stockton line passed by Fort Mason’s eastern gate. Muni’s D-Van Ness and E-Union lines penetrated The Presidio to a terminal near Letterman Army Hospital, where war wounded would soon arrive for treatment. The headquarters of the western U.S. Army defense command were only a short walk away, adjoining the main parade ground.

But these weren’t the only military facilities in the city. The U.S. government went hunting for space to house officers and offices, and took over, among other buildings, the 100 McAllister building, just a block from the saturation streetcar service of Market Street.

On the city’s central waterfront, the shipyard at Pier 70 (where some of Muni’s original streetcars had been built) took on frantic levels of activity. Up to 10,000 men and women worked three shifts a day, ultimately building 72 vessels and repairing 2,500 others during the war.

Muni didn’t serve this edge of the city, but MSRy did. They had converted their Third Street streetcar lines to buses in September 1941 but luckily had retained the tracks and wires as far south as Mariposa street. They added streetcars back to the mix, ultimately reaching the huge Bethlehem Shipyard at Pier 70 (where some of Muni’s streetcars had been built) by using Southern Pacific freight trackage next to Illinois Street. Some of MSRy’s streetcars had their cross seating ripped out and replaced with longitudinal seating against the sides (like today’s F-line Milan trams) to allow more riders to be crammed on board. These were called ‘victory cars’.

No streetcars ever reached Hunter’s Point Naval Shipyard farther south, which mushroomed in size during the second half of the war, but the federal government provided extra buses to MSRy to boost its service there.

Breaking barriers

Of course, both transit companies needed people to operate and maintain their vehicles, and many of those employees—all men, and almost all white at the time—were headed off to war. So, like other industries, they looked for new sources of labor.

Muni and MSRy both recruited women for ‘platform’ (motorman and conductor) jobs. Since those terms didn’t seem to fit women, some dubbed them ‘motorettes’ and ‘conductorettes’. But female operators faced challenges. Muni had two operators’ unions at the time. The streetcar union accepted women members—but only for ‘the duration of the war’. The bus union refused women altogether.

African-Americans had been migrating west in large numbers, seeking defense jobs. Some found employment on the city’s streetcars and buses, though not without encountering—and having to overcome—strong racism.

By her own account, a 19-year old woman named Marguerite Johnson, recently arrived from Arkansas, was the first African-American to work on San Francisco’s streetcars, hired by Market Street Railway. The account comes from the author and poet Maya Angelou, writing in I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.

Angelou is writing about herself, a George Washington High School student at the time, who lied about her age (she was actually 16) and gave a false name to win a streetcar job. All who want a clear and searing picture of wartime San Francisco should read those chapters in the book that cover it.

Angelou writes of repeated trips to the “dingy, drab” MSRy office at 58 Sutter Street, pushing back against a series of excuses to not hire her. She tells of how her determination intensified when she boarded a streetcar and “the conductorette looked at me with the usual hard eyes of white contempt.” She finally triumphed in her quest:

I was swinging on the back of the rackety trolley, smiling sweetly and persuading my charges to ‘step forward in the car, please.’ For one whole semester…I clanged and cleared my way down Market Street, with its honky-tonk homes for homeless sailors, past the quiet retreat of Golden Gate Park and along closed undwelled-in-looking dwellings of the Sunset District.

Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

Surplus in time of need

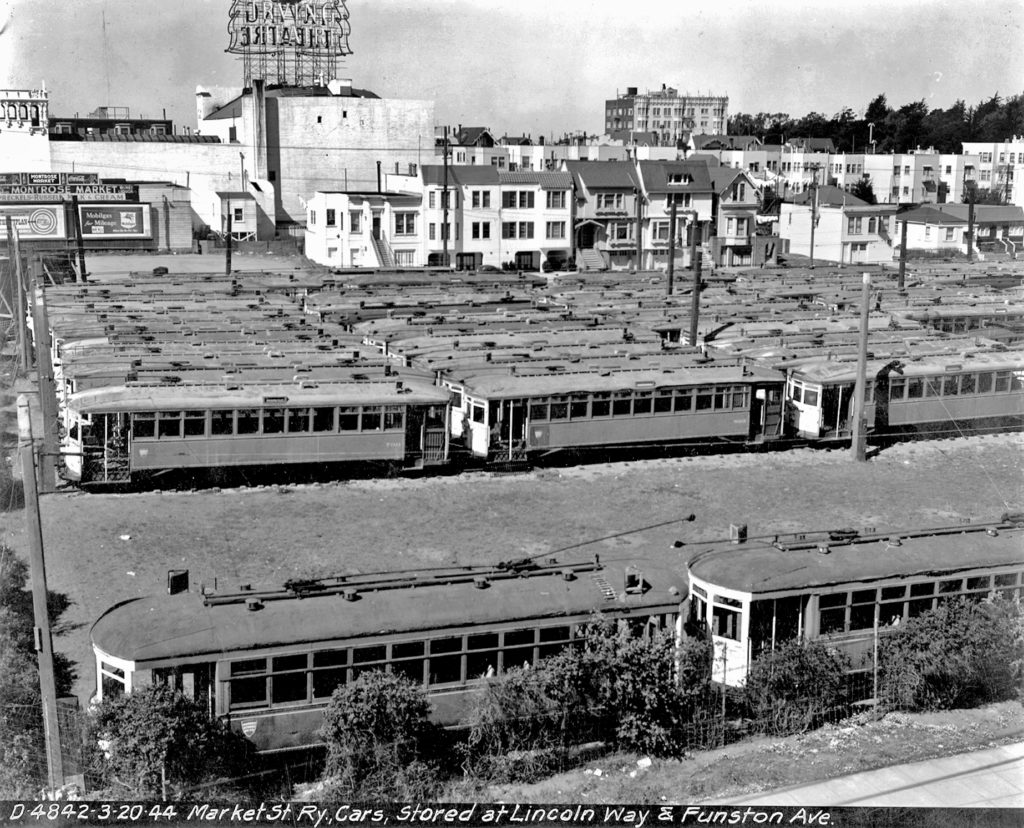

While Angelou probably worked on numerous routes as a rookie conductor, her description in her book fits the 7-Haight line that ran along Lincoln Way at the southern edge of Golden Gate Park, passing what was an anomalous sight between Funston and 14th Avenues: a block filled with sleeping streetcars at a time when every streetcar was supposedly needed.

This was MSRy’s ‘boneyard’, where unused streetcars were stored. Scores of streetcars were lined up on the ladder tracks; many of them in good condition but set up to be run by only a single operator. They had been withdrawn from service when the courts had ruled against single-operator service in San Francisco in 1938, siding with organized labor. MSRy President Samuel Kahn said these streetcars remained sidelined because of labor shortages, and if one-operator cars were allowed again, more streetcars would return to the streets. The U.S. Office of Defense Transportation appealed for the change to single-operator service, but San Francisco voters rejected it in 1943 by a margin of better than four to one, a testament to the power of labor unions in the city, even during wartime.

To some extent, Kahn’s statement was disingenuous, as Angelou’s difficulty in getting a job attests. Yet she herself pointed out the bigger problem: “Openings were going begging that paid twice the money” of a platform job, she wrote. And it was true. Both MSRy and Muni had trouble holding onto employees tempted by higher paying defense jobs.

While Muni had the full faith and credit of the City and County of San Francisco behind it, MSRy was a private company in chronic financial trouble. While a 1943 investigation by the California State Railroad Commission castigated MSRy for not returning streetcars to service, deferring maintenance on its fleet and tracks, and not paying its employees enough, it was not clear what the company could do about it. City officials were putting on a full-court press to force a merger with Muni, hardly a conducive environment for investment. Voters weren’t cooperating, though, turning down measures to buy out MSRy in November 1942 and again in April 1943, leaving the private company in a kind of limbo.

Coming together

All the while, Muni kept rolling on. While much smaller than MSRy, it wasn’t saddled with many low-revenue routes it was required to operate as a condition of a franchise from the city. And while it sounds crazy today, the difference between Muni’s five cent fare and its competitor’s seven cents drew a lot of extra riders to Muni where the companies had parallel service. (It was, after all, a 40 percent difference in an era when a nickel bought a cup of coffee.) The diversion of riders, most prominent on the Market Street lines, hurt MSRy while increasing Muni’s profits.

To meet increased demand, Muni pressed its only class of underused streetcars, the Type-J ‘dinkies’ that served the hilly E-Union, into additional service on the F-Stockton line. Still, Muni’s fleet was pressed to the limit as more and more war production jobs were created. Spare streetcars were nearby at Funston Boneyard, but they were owned by the competition.

But not for long. Finally, on May 16, 1944, San Francisco voters approved the acquisition of MSRy, on the premise that it would be paid for by Muni’s increased wartime profits. The nearly two-to-one vote came after a vigorous campaign by the new mayor, Roger Lapham, for consolidation of the systems.

The two systems officially became one at 5:00am on September 29, 1944, when Mayor Lapham piloted an old MSRy streetcar out of Muni’s Geary Division. It was a sign of things to come, because to balance the wartime loads, Muni soon pressed ex-MSRy cars into service on a couple of its original lines, including the C-Geary-California and H-Potrero.

But there wasn’t a lot to work with, as the city’s Manager of Utilities, E.G. Cahill, wrote in the May 1945 issue of Interurban News Letter.

The entire former Market Street Railway of San Francisco will have to be scrapped immediately after the war. In fact, if the war lasts too long, it will scrap itself. It is obvious that equipment, every piece of which must be dragged off to the barns for repairs 15 times in five months, is in the last stages of decrepitude. It will be a miracle if this rambling wreck of a railway can be held together for the duration, regardless of the amount of money we spend on it.

E. G. Cahill, San Francisco City and County Manager of Utilities, May 1945

Cahill was talking about facilities as well as equipment. Stretches of the MSRy track were barely useable. In fact, MSRy had convinced the federal Office of Defense Transportation to let them abandon the Guerrero Street track of the 10-line because it was so bad.

Deferred maintenance, heavy wartime loads, and just plain age (much track in the system was 40 or more years old) combined to create more wear on the streetcars and rough rides for passengers.

Of course, employees of MSRy came over to the City with the system, requiring an extensive effort to integrate workers for seniority, consolidate different kinds of shops and rationalize the assignment of equipment to car barns. Competing unions complicated the process, as we will see in our next installment.

Every one of the big 1200-class of streetcars serving MSRy’s famed interurban 40-line to San Mateo was soon repainted into Muni’s blue and gold livery, as were a few other MSRy cars. In fact, all of the old MSRy streetcars had to get some paint, because the City Charter precluded payment of royalties for the patented ‘White Front’ paint scheme to the residual MSRy shell corporation. Accordingly, the old cars, their platforms sagging from age and wartime loads, were run through the paint shops to get their ends repainted, usually Muni blue and gold, quite a clash with the still-green sides.

Painting, patching, and persevering week after week, the now-combined workforce of Muni and MSRy kept the system functioning until V-J Day, August 14, 1945, when the War in the Pacific ended.

The late Philip Hoffman, Market Street Railway’s long-time historian, remembered how he, as a 14-year old, joined the celebration that brought wall-to-wall crowds to Market Street. “I saw people climbing on the roof of streetcars and I thought, ‘This is my golden opportunity.’ So, I climbed on the roof of car 86 and rode down Market until finally the inspector at Van Ness told me to come down and I was 86’d off car 86.”

That celebration also had a very dark side. Eleven people died, including a Muni employee, and many more were assaulted in revelry gone very wrong – despicable, riotous acts.

World War II was over. Muni had made it through, though its competitor didn’t. And San Francisco emerged a stronger city, beloved by hundreds of thousands of GIs who passed through headed to and from the Pacific Theater; many promising themselves they’ve move here someday.

But though San Francisco never received an enemy bomb or shell, there was still wreckage in sight on V-J Day: its streetcar system.

- By Rick Laubscher

Installments in this series: