“This is my city and my game…You birds’ll be in New York or Constantinople or some place else. I’m in business here.” – Sam Spade

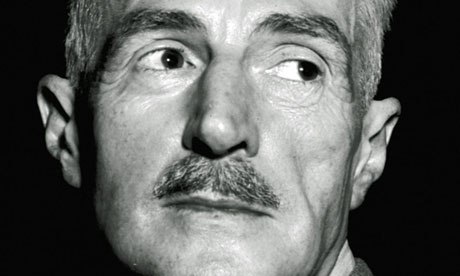

Dashiell Hammett invented the genre of the hard-boiled detective (now often called Noir) with his short stores in the magazine Black Mask and then in the most famous of his works, The Maltese Falcon, published in 1930 and widely recognized today as a seminal work of American literature.

In that novel, the main character was cynical private eye Sam Spade, who became one of the most famous characters ever in detective fiction despite appearing in only that one novel of Hammett’s. But in both Falcon and in his earlier short stories, the major supporting character is San Francisco.

When the book was written, San Francisco was Hammett’s city too, a fact made obvious from the rich detail imparted in the spare, muscular prose Hammett favored. And though they only make cameo appearances in the book, streetcars and cable cars were a constant presence in the neighborhoods traversed by Spade, Brigid O’Shaughnessy, Casper Gutman, Joel Cairo, and Wilmer Cook. By doing a little sleuthing of our own, we can extract some valuable clues into how San Franciscans like Hammett — and his creation Spade — relied on the rails to get around our town in the 1920s.

A, B, C, D, 1, 2, 3

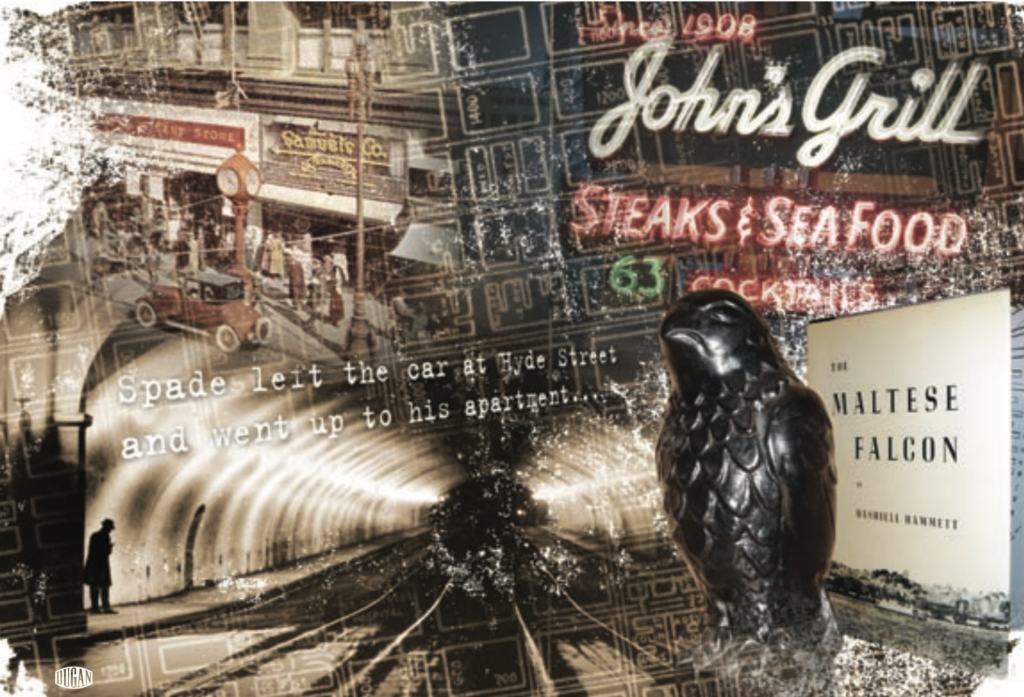

“Spade…crossed [Geary] street to board a westbound street-car. The youth in the cap boarded the same car. Spade left the car at Hyde Street and went up to his apartment. His rooms were not greatly upset, but showed unmistakable signs of being searched. When Spade had washed and had put on a fresh shirt and collar he went out again, walked up to Sutter Street, and boarded a westbound car. The youth boarded it also.”

The Maltese Falcon

In that single passage, Hammett captures the quintessence of San Francisco’s streetcar environment in the 1920s. (From actual events mentioned in the book, experts have established that the novel is set from December 6-10, 1928.)

After leaving Joel Cairo at the Geary Theater, Spade boards a gray ‘Battleship’ on the first American big-city street ever served by publicly owned streetcars. The A, B, C, and D were all trunk lines on Geary, and though they began diverging from Geary at Van Ness, Spade would’ve climbed on the first car that came along, because he was only going four blocks, almost not worth wasting a nickel on.

Then, after ascertaining that his ‘rooms’ on Post Street had been searched, Spade hikes one block up Hyde to Sutter where he would’ve boarded a streetcar owned by Muni’s fierce competitor, Market Street Railway Company. It could’ve been on the 1, 2, or 3 line; again, it didn’t matter to Spade since he was only riding a few blocks. By that time, all the Sutter cars should have sported the recently patented ‘White Front’ paint scheme, making them much more visible in the night than their fog-colored Muni counterparts.

Although the book doesn’t say so, Spade’s regular commute to his office would also have been on the Sutter streetcars. Hammett aficionado Joe Gores—an excellent mystery writer in his own right—deduced from clues in the novel that Spade’s office was in the Hunter-Dulin Building, which still stands at 111 Sutter. (Across Montgomery Street, in the Holbrook Building at 58 Sutter, were Market Street Railway Co.’s executive offices.)

Hammett as Spade

It’s quite clear that Hammett set The Maltese Falcon in places he knew well from his own daily experiences in San Francisco. His ‘rooms’, for example, were more than likely Hammett’s own apartment of the period, 891 Post Street, #401. In 1928, this corner, Hyde and Post, was almost as rara avis as the black bird everyone was pursuing in the novel: a downtown intersection without any streetcar or cable car tracks at all, making it a relative oasis of serenity, largely free from the near-constant growl of nearby streetcar motors or clatter of track joints. Since this apartment is where Hammett wrote The Maltese Falcon, perhaps that lack of streetcars in the streets immediately below is why they appear only rarely in the book.

Hammett (and Spade) had plenty of transit options within walking distance, though, with the Geary and Sutter lines each one block away, as was the 10th & Montgomery Streets line, which ran up Post as far as Leavenworth, a block east. However, that line was so unimportant that it was usually operated by only one car (identical to preserved Car 578) to protect its franchise for Market Street Railway, and never even received a route number. The Montgomery portion of the was discontinued without replacement in 1927; the rest of the line was gone by 1932.

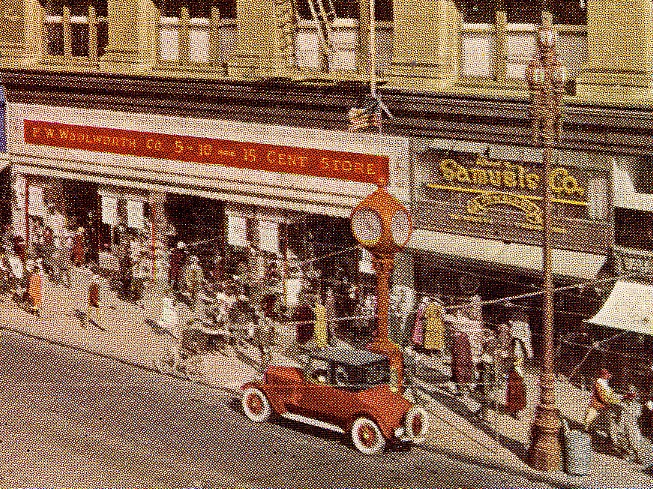

In the real world, Hammett would have used streetcars every day to get around town, as he had no automobile. At the beginning of his literary career, when he was writing short stories for Black Mask, the leading detective pulp fiction magazine of the day, his ‘day job’ was working as an advertising copywriter for Albert S. Samuels Jewelers at 895 Market, in the Lincoln Building at the corner of Fifth (now Westfield Center shopping mall, housing Nordstrom).

For five years earlier in the 1920s, he mostly lived with his wife and young daughter at 620 Eddy, between Larkin and Polk. ‘Mostly’ because Hammett was tubercular, and when the disease was active, he stayed in other nearby rooms to avoid the risk of infecting his family. In those days, before the 31-Balboa opened, Eddy was served by the westbound 4-Turk & Eddy line, which ran from the Ferries to the Richmond District. Hammett’s regular commute to the office would probably have taken him a block south to catch the inbound 4-car on Turk. That line made a clumsy dogleg when it reached Market, jogging a block north to Eddy before heading east again to merge into Market’s ‘Roar of the Four’ streetcar maelstrom at Powell.

For Hammett’s job at Samuels, it would’ve been quicker to jump off the car at Turk and Market and walk the short block to Fifth. For his previous job, as a Pinkerton detective, he would have stayed on the car until Eddy and Market (an intersection eradicated by the excavation of Hallidie Plaza as part of the BART project in the 1970s). Alighting from the car, he would have passed the Powell cable car turntable, sitting in the middle of an active street with no tourists waiting in line, and entered the ornate Flood Building at 870 Market Street, there to ride the open-sided birdcage elevators to the Pinkerton office in Suite 314 (five floors below Market Street Railway’s office today, Suite 803).

After work, if Hammett chose to grab a drink or meal at John’s Grill—then, as now, next door to the Ellis Street entrance of the Flood Building—he might have gotten home by jumping a 20-line streetcar westbound to Hyde, where the line jogged a block north to continue west on O’Farrell. From there, it was a two-block walk to 620 Eddy.

A ‘Pink’

Tagged as a communist during the witch hunts following World War II, Hammett was known as a ‘Pink’ in the early ’20s for a completely different reason: it was the standard term for Pinkerton detectives. It was this job that gave Hammett the grist for his detective novels. His first protagonist was a rotund nameless detective known as the ‘Continental Op’ after the fictional San Francisco detective agency the character served as an operative. The short stories featuring the Op built Hammett’s confidence and reputation.

Many of the Op stories were set in San Francisco and featured the same detailed city flavor as The Maltese Falcon. In The Whosis Kid, Hammett describes the Op tailing a suspect as he left the boxing matches at the Western Addition arena called Dreamland (later the site of Winterland). ‘The Kid walked down to Fillmore Street, took on a stack of wheats, bacon and coffee at a lunch room, and caught a No. 22 car. He—and likewise I—transferred to a No. 5 car at McAllister Street, dropped off at Polk…” (The same trip can be made on the same lines today, only on trolley buses instead of streetcars.)

In The House in Turk Street, the Op tries to gain information by spinning a story to residents that he was looking for witnesses who might have seen his (phony) client ‘thrown from the rear platform of a street car last week’—a common enough occurrence in those days to be credible.

As a Pink, Hammett worked on a variety of assignments that contributed flavor to his later writing. One of his cases, though, never was fictionalized: the holdup of the California Street Cable Railroad—presumably at Cal Cable’s offices at California & Hyde. According to William F. Nolan’s biography, Hammett: A Life at the Edge, he took on this case, among others, as extra work because he needed the money. In October 1921, he became a father when his daughter, Mary Jane, was born at St. Francis Hospital, just a block from the Cal Cable offices.

Hammett and cable cars

Cable Cars are never mentioned in The Maltese Falcon, although action takes place both on Powell Street (in a hotel dubbed the St. Mark, though from its location it is clearly the St. Francis), and in Brigid O’Shaughnessy’s apartment, likely located at 1201 California Street. Given Hammett’s familiarity with them and his penchant for local color, this may seem like an odd omission. It is possible that Hammett wanted to paint an urban landscape familiar to big-city dwellers all over America, and while streetcars were ubiquitous across the US in those days, cable cars were then running only in San Francisco, Seattle and Tacoma. It’s also possible he didn’t want to clutter his prose by explaining what a cable car was.

Whatever his reasons, Hammett himself would have ridden his fair share of cable cars in those days. For a brief time in 1926, he and his family lived at 1309 Hyde Street, between Clay and Washington. To cable car aficionados even then, this was a famous stretch of Hyde, carrying the last completely new cable car line opened in the city.

When the O’Farrell, Jones & Hyde line opened in 1891, the rules required that the cable on new lines be ‘inferior’ (pass underneath) every older cable line it crossed. This meant that the gripman had to drop the ‘rope’ (cable) at every cable crossing to avoid snagging the ‘superior’ cable of the older line it was intersecting—22 times in all on one round trip for this newest line. In this particular stretch near Hammett’s apartment, the Hyde line crossed older lines at five successive intersections: California, Sacramento, Clay, Washington, and Jackson. (The tribulation of operating this line was memorialized by Gelett Burgess in 1901 in his poem The Ballad of the Hyde Street Grip.)

Going north on Hyde was a lurching, jerky ride, as the first four blocks of this stretch were uphill, requiring the rope to be dropped and picked up again at each intersection before cresting the hill at Washington and coasting across Jackson. Southbound on Hyde, however, was a freewheeling joyride after Jackson, all the way past the carhouse on the southwest corner of California and Hyde (a supermarket today). Watch out, though: the line turned east (and uphill) at Pine, so the gripman had to be sure to take the rope after the carhouse.

Hammett might have enjoyed this ride when he was living on Hyde, because the line then jogged down Jones to O’Farrell, a two-block walk from Samuels. (This portion of the great Hyde trackage disappeared in 1954.) Perhaps an even faster solution would have been jumping on a Washington-Jackson cable car a half-block from his house and riding directly to Powell and Market, with the jewelry store just across the street. Samuels later moved across Market to a location just east of the Flood Building. Its massive street clock made the move across Market too, and is today the only remnant of the family-owned jewelry firm that billed itself as ‘The House of Lucky Wedding Rings’.

It does not appear that Hammett wrote that slogan as part of his Samuels job. It would have been ironic if he had, for his own marriage was on the rocks. After leaving the Hyde Street apartment and his family for 891 Post, he rarely lived together with his wife again, famously beginning an affair with the playwright Lillian Hellman just a few years later, a relationship that would last until his death in 1961.

During an earlier family split, Hammett lived for a time at 20 Monroe Street, an alley off Bush near Stockton, while his wife and daughter lived across the bridgeless Golden Gate in San Anselmo. He visited them frequently on weekends, likely using cable cars for the first part of the journey: walk two blocks north to California Street for a ride on the Cal Cable, with a free transfer to the company’s Hyde line, then onto the Northwestern Pacific ferry at the Hyde Street Pier, switching to the electric interurban train at Sausalito for the rest of the trip.

Murder atop Stockton Tunnel

Of more import to the literary world, during his time at 20 Monroe Street, Hammett daily passed the scene of the most famous fictional crime in San Francisco history—a crime of his own creation.

To reach Samuels, Hammett would have either walked three-quarters of a block west on Bush to catch a Powell cable car, or jogged a few feet east on Bush to descend the stairs at the south portal of the Stockton Tunnel, taking an F-Stockton Muni streetcar to its terminal at Market, then walking a block to his office.

Certainly, then, Hammett was quite familiar with the rather foreboding portal, constantly rent by the echoes of Muni ‘A-type’ streetcars (including preserved car No. 1) roaring through the tunnel. Though the novel doesn’t mention it, that ear-splitting sound of streetcars emerging from the portal would have been an effective mask for the sound of the bullet from the Webley-Fosbery revolver in Brigid O’Shaughnessy’s hand. That bullet, of course, killed Spade’s partner, Miles Archer, to open The Maltese Falcon, setting off the entire adventure. The scene of the crime was the dark alley named Burritt Street, just across Bush from the apartment on Monroe. In those days, there was a steeply sloped vacant lot between Burritt and the tunnel portal, down which the dying Archer tumbled.

Up in the world

Even before The Maltese Falcon was published as a book in February 1930, its successful serialization in Black Mask was bringing Hammett great success. His last San Francisco address, 1155 Leavenworth, showed he was literally moving up in the world, onto the upper slopes of Nob Hill, between California and Sacramento Streets. Here again, he was sandwiched among three cable car lines, but by now he was well off enough to take taxis when he needed to get around town. He left town for good in October 1929, bound for New York and then Hollywood before writer’s block truncated his career.

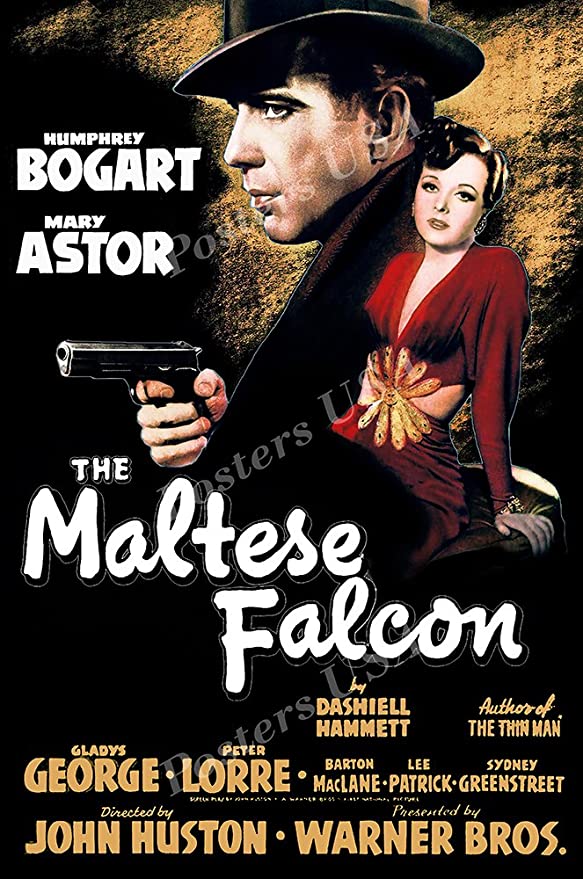

Of course, Hammett’s writing also led to one of the most loved movies ever made. The Humphrey Bogart version of The Maltese Falcon was actually the third version of the book put to celluloid, and by far the most faithful. The first-time director, John Huston, is said to have created the screenplay by simply converting the book’s dialogue into script form, using the book’s narrative as screen direction. There was, of course, some necessary editing and a little simplification, including the removal of the book’s streetcar scene. Few movies of the day were filmed outside Los Angeles, and except for the first panoramic stock shot of the City from the Bay, The Maltese Falcon was filmed on Hollywood sound stages or back lots.

Hammett’s legacy includes some of the most vivid prose ever penned in a San Francisco setting. It also conveys enduring insight into the way transit served as the vital circulation system bringing mobility to San Franciscans—just as Muni does today.

Written by Rick Laubscher; photos from Market Street Railway Archive unless otherwise noted. If you’d like to keep stories like this coming, please consider supporting us.

For those with a New York Times subscription, check out this great 2014 story retracing Hammett’s haunts.